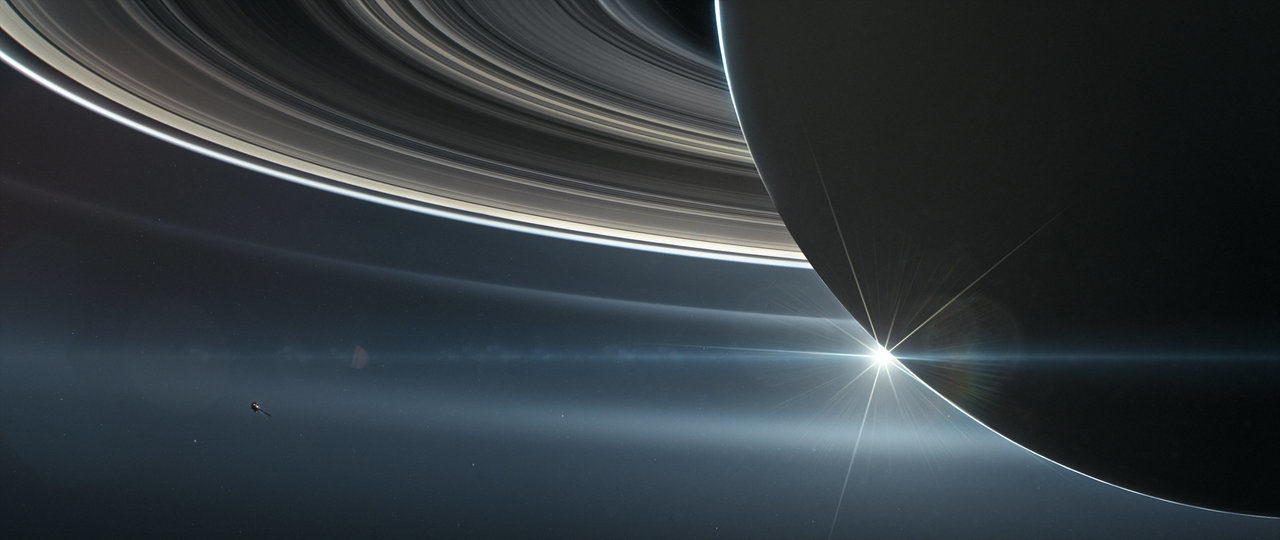

Backlit Saturn. › Full image and caption

As the Cassini spacecraft neared the end of a long journey rich with scientific and technical accomplishments, its legacy was an already powerful influence on future exploration.

In revealing that Enceladus has essentially all the ingredients needed for life, the mission energized a pivot to the exploration of "ocean worlds" that has been sweeping planetary science over the past couple of decades.

Jupiter's moon Europa has been a prime target for future exploration since NASA's Galileo mission, in the late 1990s, found strong evidence for a salty global ocean of liquid water beneath its icy crust. But the revelation that a much smaller moon like Enceladus could also have not only liquid water, but chemical energy that could potentially power biology, was staggering.

Many lessons learned during Cassini's mission are being applied in planning NASA's Europa Clipper mission, planned for launch in the 2020s. Europa Clipper will make dozens of flybys of Jupiter's ocean moon to investigate its possible habitability, using an orbital tour design derived from the way Cassini explored Saturn. The mission will orbit the giant planet (Jupiter in this case) using gravitational assists from large moons to maneuver the spacecraft into repeated close encounters, much as Cassini used the gravity of Titan to continually shape the spacecraft's course.

In addition, many engineers and scientists from Cassini are serving on Europa Clipper and helping to shape its science investigations. For example, several members of the Cassini Ion and Neutral Mass Spectrometer team are developing an extremely sensitive, next-generation version of their instrument for flight on Europa Clipper. What Cassini learned about flying through the plume of material spraying from Enceladus will be invaluable to Europa Clipper, should plume activity be confirmed on Europa.

By pulling back the veil on Titan, Cassini ushered in a new era of extraterrestrial oceanography—plumbing the depths of alien seas—and delivered a fascinating example of earthlike processes occurring with chemistry and temperatures very different from our home planet.

In the decades following Cassini, scientists hope to return to the Saturn system to follow up on the mission's many discoveries. Mission concepts under consideration include spacecraft to drift on the methane seas of Titan and fly through the Enceladus plume to collect and analyze samples for signs of biology.

Atmospheric probes to all four of the outer planets have long been a priority for the science community, and the most recent Planetary Science Decadal Survey continues to support interest in sending such a mission to Saturn. By directly sampling Saturn's upper atmosphere during its last orbits and final plunge, Cassini laid the groundwork for an eventual Saturn atmosphere probe.

Farther out in the solar system, scientists have long had their eyes set on exploring Uranus and Neptune. So far, each of these worlds has been visited by only one brief spacecraft flyby (Voyager 2, in 1986 and 1989, respectively). Collectively, Uranus and Neptune are referred to as ice giant planets. In spite of that name, relatively little solid ice is thought to be in them today, but it is believed there is a massive liquid ocean beneath their clouds, which accounts for about two-thirds of their total mass. This makes them fundamentally different from the gas giant planets, Jupiter and Saturn (which are approximately 85 percent gas by mass), and terrestrial planets like Earth or Mars, which are basically 100 percent rock. It's not clear how or where ice giant planets form, why their magnetic fields are strangely oriented, and what drives geologic activity on some of their moons. These mysteries make them scientifically important, and this importance is enhanced by the discovery that many planets around other stars appear to be similar to our own ice giants.

A variety of potential mission concepts are discussed in a recently completed study, delivered to NASA in preparation for the next Decadal Survey—including orbiters, flybys and probes that would dive into Uranus' atmosphere to study its composition. Future missions to the ice giants might explore those worlds using an approach similar to Cassini's mission.