News | March 28, 2019

Hubble Watches Spun-Up Asteroid Coming Apart

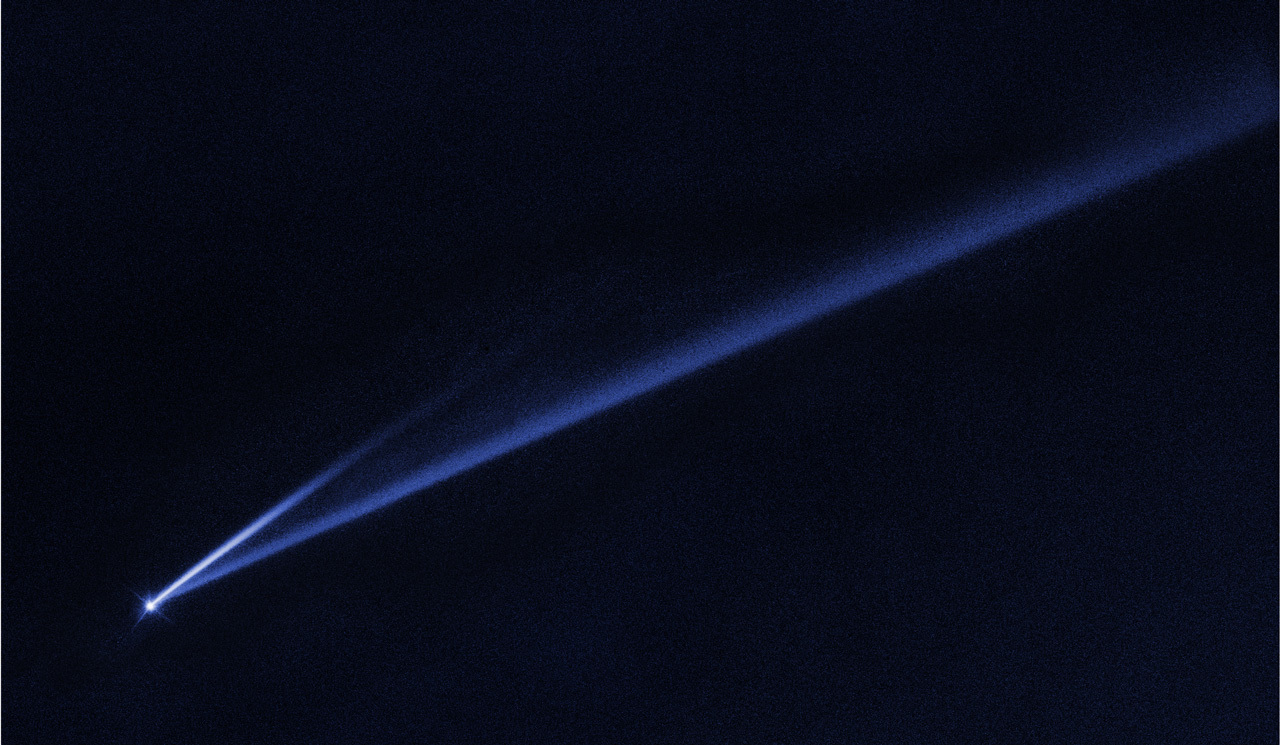

This Hubble Space Telescope image reveals the gradual self-destruction of an asteroid, whose ejected dusty material has formed two long, thin, comet-like tails. The longer tail stretches more than 500,000 miles (800,000 kilometers) and is roughly 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) wide. The shorter tail is about a quarter as long. The streamers will eventually disperse into space. Credit: NASA, ESA, K. Meech and J. Kleyna (University of Hawaii), and O. Hainaut (European Southern Observatory)

A small asteroid has been caught in the process of spinning so fast it’s throwing off material, according to new data from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and other observatories.

Images from Hubble show two narrow, comet-like tails of dusty debris streaming from the asteroid (6478) Gault. Each tail represents an episode in which the asteroid gently shed its material — key evidence that Gault is beginning to come apart.

Discovered in 1988, the 2.5-mile-wide (4-kilometer-wide) asteroid has been observed repeatedly, but the debris tails are the first evidence of disintegration. Gault is located 214 million miles (344 million kilometers) from the Sun. Of the roughly 800,000 known asteroids between Mars and Jupiter, astronomers estimate that this type of event in the asteroid belt is rare, occurring roughly once a year.

Watching an asteroid become unglued gives astronomers the opportunity to study the makeup of these space rocks without sending a spacecraft to sample them.

“We didn’t have to go to Gault,” explained Olivier Hainaut of the European Southern Observatory in Germany, a member of the Gault observing team. “We just had to look at the image of the streamers, and we can see all of the dust grains well-sorted by size. All the large grains (about the size of sand particles) are close to the object and the smallest grains (about the size of flour grains) are the farthest away because they are being pushed fastest by pressure from sunlight.”

Gault is only the second asteroid whose disintegration has been strongly linked to a process known as a YORP effect. (YORP stands for “Yarkovsky–O'Keefe–Radzievskii–Paddack,” the names of four scientists who contributed to the concept.) When sunlight heats an asteroid, infrared radiation escaping from its warmed surface carries off angular momentum as well as heat. This process creates a tiny torque that can cause the asteroid to continually spin faster. When the resulting centrifugal force starts to overcome gravity, the asteroid’s surface becomes unstable, and landslides may send dust and rubble drifting into space at a couple miles per hour, or the speed of a strolling human. The researchers estimate that Gault could have been slowly spinning up for more than 100 million years.

Piecing together Gault’s recent activity is an astronomical forensics investigation involving telescopes and astronomers around the world. All-sky surveys, ground-based telescopes, and space-based facilities like the Hubble Space Telescope pooled their efforts to make this discovery possible.

The initial clue was the fortuitous detection of the first debris tail, observed on Jan. 5, 2019, by the NASA-funded Asteroid Terrestrial-Impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) telescope in Hawaii. The tail also turned up in archival data from December 2018 from ATLAS and the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS) telescopes in Hawaii. In mid-January, a second shorter tail was spied by the Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope in Hawaii and the Isaac Newton Telescope in Spain, as well as by other observers. An analysis of both tails suggests the two dust events occurred around Oct. 28 and Dec. 30, 2018.

Follow-up observations with the William Herschel Telescope and ESA’s (European Space Agency) Optical Ground Station in La Palma and Tenerife, Spain, and the Himalayan Chandra Telescope in India measured a two-hour rotation period for the object, close to the critical speed at which a loose “rubble-pile” asteroid begins to break up.

“Gault is the best ‘smoking gun’ example of a fast rotator right at the two-hour limit,” said team member Jan Kleyna of the University of Hawaii in Honolulu.

An analysis of the asteroid’s surrounding environment by Hubble revealed no signs of more widely distributed debris, which rules out the possibility of a collision with another asteroid causing the outbursts.

The asteroid’s narrow streamers suggest that the dust was released in short bursts, lasting anywhere from a few hours to a few days. These sudden events puffed away enough debris to make a “dirt ball” approximately 500 feet (150 meters) across if compacted together. The tails will begin fading away in a few months as the dust disperses into interplanetary space.

Based on observations by the Canada–France–Hawaii Telescope, the astronomers estimate that the longer tail stretches over half a million miles (800,000 kilometers) and is roughly 3,000 miles (4,800 kilometers) wide. The shorter tail is about a quarter as long.

Only a couple of dozen active asteroids have been found so far. Astronomers may now have the capability to detect many more of them because of the enhanced survey capabilities of observatories such as Pan-STARRS and ATLAS, which scan the entire sky. “Asteroids such as Gault cannot escape detection anymore,” Hainaut said. “That means that all these asteroids that start misbehaving get caught.”

The researchers hope to monitor Gault for more dust events.

The team’s results have been accepted for publication by The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and ESA (European Space Agency). NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in Washington, D.C.

For more information about 6478 Gault and Hubble, visit: http://hubblesite.org/news_release/news/2019-22 and http://www.nasa.gov/hubble

Donna Weaver / Ray Villard

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md.

410-338-4493 / 410-338-4514

dweaver@stsci.edu / villard@stsci.edu

Claire Andreoli

NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

301-286-1940

claire.andreoli@nasa.go