News | December 31, 2018

New Horizons Spacecraft Homing in on Kuiper Belt Target

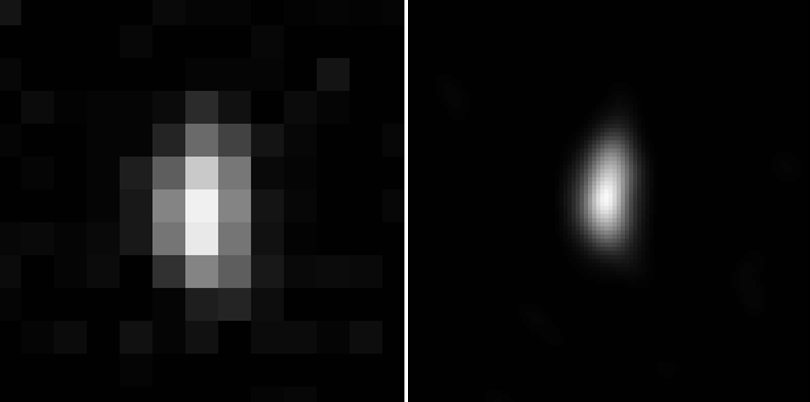

Just over 24 hours before its closest approach to Kuiper Belt object Ultima Thule, the New Horizons spacecraft has sent back the first images that begin to reveal Ultima’s shape. The original images have a pixel size of 6 miles (10 kilometers), not much smaller than Ultima’s estimated size of 20 miles (30 kilometers), so Ultima is only about 3 pixels across (left panel).

Only hours from completing a historic flyby of Kuiper Belt object 2014 MU69, nicknamed Ultima Thule, NASA's New Horizons spacecraft is on course and ready to gather scientific data on the small object's geology, composition, atmosphere and more. Closest approach takes place in the early morning hours of New Year's Day — 12:33 a.m. EST — marking the event as the most distant exploration of worlds ever completed by humankind.

After a 13-year journey, the piano-sized spacecraft has covered a distance of four billion miles to reach Ultima Thule in the Kuiper Belt — a donut-shaped region of ancient, rocky bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. This vast region of space contains potentially billions of small objects left over from the formation of the solar system that could hold keys to understanding planetary formation.

"Even less than a day away, Ultima Thule remains an enigma to us, but the final countdown has begun," said New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado. "What we'll very soon learn about this primordial building block of our solar system will exponentially expand our knowledge of this relatively unknown third region of space."

New Horizons launched in January 2006 on a nine-year mission to Pluto, which it reached in July 2015, taking numerous pictures and scientific measurements as it flew by the dwarf planet. The spacecraft returned stunning images of an icy landscape and an eccentric array of moons that were previously only imagined. NASA later extended the mission to include additional Kuiper Belt studies.

Even less than a day away, Ultima Thule remains an enigma to us, but the final countdown has begun. What we'll very soon learn about this primordial building block of our solar system will exponentially expand our knowledge of this relatively unknown third region of space.

Using the Hubble Space Telescope, New Horizons team members discovered 2014 MU69 in the path of the spacecraft which was selected as the next mission target. This time, however, the spacecraft will fly three times closer to the target than it did to Pluto. Although not the official name for MU69, the name Ultima Thule was selected from an online naming contest that translates to "beyond the known world."

Now a billion miles beyond Pluto, New Horizons will fly by Ultima just 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) from the object's surface, providing the first close-up look at what scientists consider to be one of the ancient building blocks of the planets.

From New Horizons' location, a radio transmission traveling at light speed requires just over six hours to reach Earth. The spacecraft will not be in contact with Earth during close approach but is programmed to send a signal home on the morning of Jan. 1 to indicate its health and whether it recorded all the expected data. The mission team expects the data to be returned over the next 20 months, with an additional year of data analysis and archiving.

"The spacecraft is in great health and the team is ready," said Helene Winters, New Horizons project manager from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. "This flyby is the culmination of years of careful planning and hard work, and we can't wait to transform Ultima into a real world."

The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, designed, built and operates the New Horizons spacecraft, and manages the mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. The Southwest Research Institute, based in San Antonio, leads the science team, payload operations and encounter science planning. New Horizons is part of the New Frontiers Program managed by NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama.

Follow the New Horizons mission on Twitter and use the hashtags #UltimaThule, #UltimaFlyby and #askNewHorizons to join the conversation. Live updates and links to mission information will be also available on http://pluto.jhuapl.edu and www.nasa.gov.