| |

|

| |

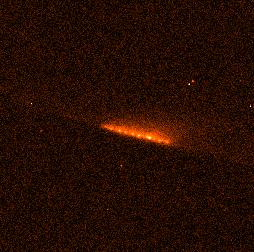

Image

taken by Mats Lindgren at the European Southern

Observatory in Chile.

Image taken on March 28, 1993, just 4 days

after it was discovered.

|

On the night of March 24, 1993, Eugene and Carolyn

Shoemaker and David Levy discovered a strange

looking comet from a photograph taken from the

0.4 meter Schmidt telescope in Palomar Observatory

in Califonia. The comet was named Comet Shoemaker-Levy

9 after the discoverers, the ninth comet discovered

by this team. The comet was very elongated, and

it turned out that comet had been pulled apart

due to tidal forces from an extremely close flyby

of Jupiter on July 8, 1992. Twenty-one separate

fragments were eventually identified. By April

5, 1993, enough observations of the comet have

been made to better define the comet's orbit,

and it was surprisingly found to be in orbit around

Jupiter. By May 25, additional observations helped

refined the orbit further, and a exciting new

development came forth: Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9

could possibly impact Jupiter in July 1994! By

June 1993, the comet's orbit was well determined

and the impacts into Jupiter would definitely

occur.

|

Hubble

image taken in May 1994. The fragments were

named from the letters of the alphabet in

the order they would impact on Jupiter.

|

With one year's advance notice, astonomers and

observatories made plans to observe this unique

event. This would mark the first time that a collision

between two solar system bodies would be observed.

Most astronomers downplayed the event to the public,

mainly due to past disappointments with a couple

of expected bright comets in the previous two

decades that did not live up to expectations.

Astronomers noted that the impacts were very unusual,

but they warned that the effects of the impacts

of the comet would probably not be visible to

Earth except by the largest telescopes. Also,

the impacts would occur on the night side of Jupiter,

out of direct view from Earth. The 21 fragments

would hit Jupiter over a one week period starting

on July 16, 1994, and everyone waited anxiously

for that day to arrive.

| |

|

| |

Calar

Alto Observatory image of the first impact

- July 16, 1994

The first image of the comet collision to

appear on the Internet

|

When the first impact hit(called Fragment A),

a plume sighting from the impact was reported

by Calar Alto Observartory in the Canary Islands

and the South African Astronomical Observatory

(SAAO). The Calar Alto and SAAO images of the

plume were quickly placed on the Internet just

a few hours after they were taken. The Calar Alto

images were taken in the infrared, and there was

no doubt of the first impact - showing a huge

explosion off the side of Jupiter. The Hubble

Space Telescope also took images of the impact,

but it took longer to download the images from

the spacecraft down to Earth. During a live NASA

press conference, Eugene and Carolyn Shoemaker

had mentioned the possible plume sigthings and

were anxiously awaiting the Hubble image, unaware

that images confirming the impacts were already

on the Internet. When the Hubble images did arrive,

a joyous Heide Hammel ran onto the stage with

the good news. Hubble had also detected the plume,

and showed the impact site on Jupiter as it rotated

into view - a feature that appeared as a black

eye on the top of the Jovian cloudtops. The first

impact was more visible than what everyone had

imagined, and everyone then knew they were in

for a week long extravaganza for the remaining

impacts. Comet fever had set in.

|

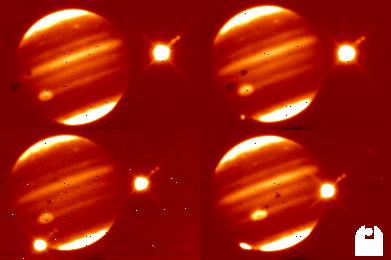

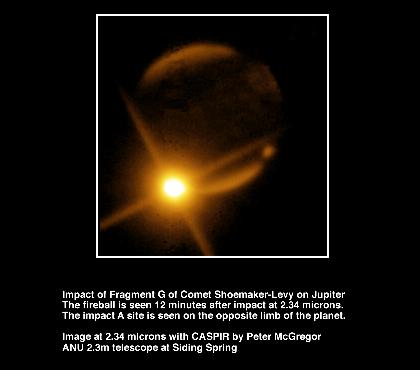

| Spectacular

image taken from the Mount Stromlo and Siding

Observatory in Australia on July 18, 1994.

Fragment G was one of the larger fragments

of the comet. |

Everyone around the world with a telescope were

now viewing Jupiter in earnest. The impact sites

were visible even fom the smallest amature telescopes.

A Internet frenzy ensued as hundreds of images

were made available on the World Wide Web. The

21 impacts were happening around the clock, so

someone around the world was able view each impact.

The plumes were particularly prominent in the

infrared, often oversaturating the infrared detectors,

but displaying spectacular images of the impact.

By sheer coincidence, the Galileo spacecraft,

enroute to Jupiter, was in position to view the

impact sites directly and took the only direct

measurements of the comet collisions.

|

Image

showing the impact of Fragment W taken by

the Galileo spacecraft on July 22, 1994.

|

| Last updated

November 26, 2003 |

|