Susan Finley

Test Engineer - NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL)

Fresno High School | Fresno, California

Scripps College | Claremont, California

Art

I didn't know anything about space. Sputnik hadn't gone up yet. I just liked math and engineering. The company I went to work for, Convair, was making rockets. It was in the space industry and they were military rockets.

I wanted to be an architect. I couldn't afford to go to a school with architecture, but I thought I could go learn art. It turns out, no, you can't learn art. I would have had to start all over again in engineering. So, I went [to college] for three years, and then I went out and got a job.

I've always liked math. I was good at math. I had a lot of part-time jobs – retail and office work. I knew I didn't like any of those things, so I went to an engineering company and I applied for a typing job, which I didn't do very well. But it turns out they needed a [human] computer. I'd had some experience working for a math professor. They asked me if I liked numbers and I said, "Oh, I like numbers much better than letters." So they put me to work as a computer. There were two of us to support 40 engineers. I just seemed to pick it up right away. Many years later I realized that it might have been a summer school class I took at Berkeley in philosophy, called "logic” – I really liked that class and it's really like programming.

I've been here [at JPL] since '58, but I took several years off in the middle, so I've been here 51 years now. I got married – just after Sputnik actually – and the commute to my job was much longer. I decided it was dangerous. I was driving on a really foggy day and it was dangerous. So, I thought I would try to find a job closer to home. Because my husband went to Caltech, he knew about JPL. He said, “Why don't you go there and apply?” And I did. They needed human computers too. It was two days before we launched Explorer 1 [on Jan. 31, 1958].

In my current job, I work in a group that makes receivers for NASA’s Deep Space Network. They're what's called open-loop receivers. We do a lot of science, and we also do navigation. I test all of the stuff we build. We also built the communications array used by JPL for spacecraft telemetry. I test a lot, and then I figure out what went wrong when it's delivered and doesn't work.

They need a degree. They certainly need to do well at school. (I would not be hired now at all, given the education I started with.) They need to really like it – I feel my job is fun, and that's why I go back every day and why I keep learning things because it's fun. You really have to like it, not just do it to make money, or to get into an industry that's a good one. But to really like math and science and working with people as a team, because we do a lot of that. It's very important.

I got married. Then I got pregnant and had a son, and I expected to have that as my career for the rest of my life. Then I got, I'd say, "not well"…I got very depressed. I was encouraged to go back to work. I had another son. When my younger son was 3, and able to go to nursery school, I went back to work. I went back to JPL. They found a job for me. By then we had big electronic computers. Before I went to work, I got a user's manual and learned that, so I was just able to go right back to work.

That was my life challenge: not working, not being with people, not being challenged.

Betty Friedan [co-founder of the National Organization for Women] inspired me back when I went back to work. She was the biggest influence. My parents always supported me. I never had the problem of somebody telling me I couldn't do something. I was lucky my math teachers were women in high school. I was always supported for what I wanted to do.

My favorite one was the Venus [Vega] Balloon. That was a French project on a Russian spacecraft – actually two of them. I got to work on pointing the DSN antennas for the spacecraft and changing the software a little bit. Watching the signal come down – I actually jumped up and down because I was so happy, of course. It was a very, very small project. We worked with the French – you were never allowed to communicate with the Russians at that point.

We did so well at getting to Venus that the Russians asked us to get them to Halley's comet too. So, the DSN tracked the two Vega spacecraft to Halley's comet. I worked on that too.

I have a funny story about that. When they asked me to work on it, I said, "I don't know. It's an awful lot of pressure, so I have two requirements. One is that somebody will check my work every time. The other one is that I get on lab parking." They actually were able to do it. I had on lab parking for the rest of that mission.

I love to eat. I like to cook. I love to go out to restaurants. I like to go to the symphony, and ballet, and theater. I don't like to exercise. I love to travel. I love the Caribbean.

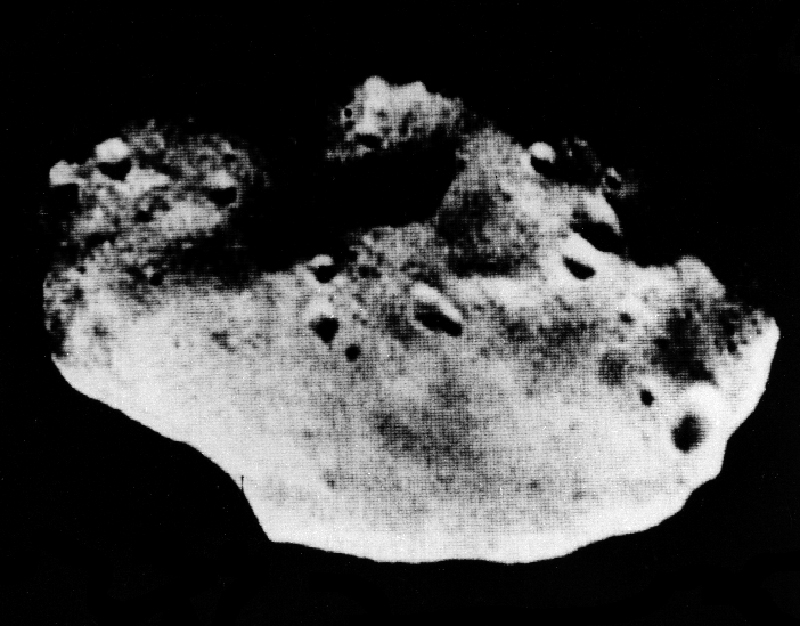

My favorite one really is a photo of Phobos, which is a moon of Mars. It was taken in the early ‘70s. The reason it's my favorite is that a friend of mine did all the calculations to figure out how to point the antenna on the spacecraft. To me, it was so magical that you could zoom by this little rock and be able to figure out how to point the antenna and take a picture.

Planetary science is a global profession.