Lindsay Hays

Program Scientist

Lindsay Hays is a Program Scientist in the Planetary Science Division (PSD) at NASA Headquarters. She is the Deputy Program Scientist for the Astrobiology Program and the Program lead for Organizational Excellence. Lindsay is also the lead Program Officer for the Exobiology and Habitable Worlds research program, and the PSD representative for the Future Investigators in NASA Earth and Space Science and Technology (FINESST) program for graduate research.

Lindsay first worked at NASA as an undergraduate summer intern for two summers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. For her graduate and postdoctoral work, using organic geochemistry, she studied lipid biomarkers for environmental conditions at major biological transition points in Earth’s history including mass extinction and radiation events. After this time in academic research, she returned to NASA as a one-year postdoctoral fellow at NASA Headquarters in the Astrobiology Program where she served as the Editor-in-Chief for the 2015 Astrobiology Strategy. She then returned to JPL, working in the Mars Program Office where she was the Sample Return Science System Engineer and also worked on science activities for Humans to Mars.

Lindsay earned her bachelor’s and doctorate degrees from the Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with her PhD thesis research titled “Biogeochemical Proxies for Environmental and Biotic Conditions at the Permian-Triassic Boundary”. After graduate school, Lindsay was a postdoctoral researcher at Harvard University, where she received the Agouron Geobiology Postdoctoral Fellowship, and a NASA Postdoctoral Management Program fellow at NASA HQ.

Lindsay enjoys being outdoors – running or hiking, whether the weather cooperates or not – and cooking, baking, and generally experimenting in the kitchen. She is often joined in these adventures by her husband and two young children.

Please direct questions or corrections on this page to SARA@nasa.gov

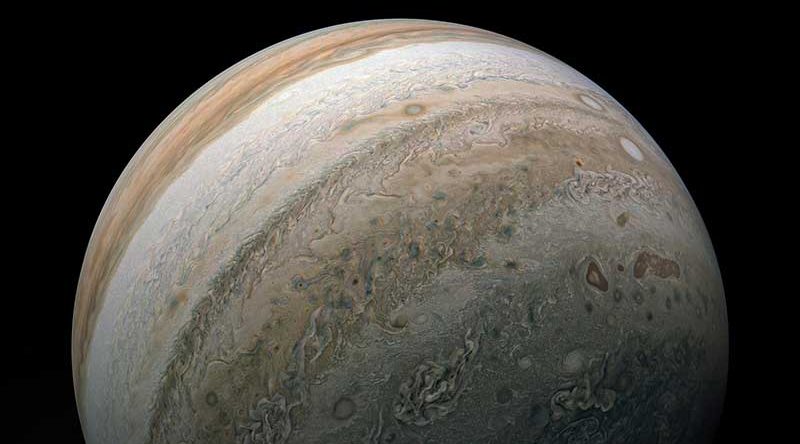

Lidsay Hays is from Jupiter, Florida – a great place to be from if you're interested in the space program. Not only does it share a name with the largest planet in our solar system, but it’s also just a few of hours' drive south of Kennedy Space Center. So Lindsay grew up watching contrails from NASA’s space shuttles launching into orbit. But it was a book she picked up when she was an 8-year-old that actually led her to her career as a program officer for NASA Exobiology and deputy program scientist for NASA's Astrobiology Program. In her profile, she shares how she landed at NASA and how she managed to keep up with Jane Austen along the way.

It was actually a random book that I picked up at the library that talked about how you could see into the past by looking at stars that were really, really far away. The idea was – because light travels one light-year per year — that when you look at stars that are really, really far away, you're actually looking at light that came from a long time ago.

The concept that we can look billions of years into the past by looking at stars, and realizing just how big space was, and just how much there was out there, and how much different stuff existed in the universe – some of which we think we understand and some of which is still beyond our capabilities to understand – that totally blew my mind as an 8-year-old. And still, it's one of those things when I start thinking deeply about it, it's just so cool.

So, it was just picking up a random science book about the vastness of space and I was totally hooked.

When I was in college, I knew I was interested in the way we can look at the history of our planet, Earth, and the history of life on this planet, and that neither of those things is a story in isolation. The history of life on our planet is the history of both the planet and the history of life. And those two things – the surface of the planet and the living things on it – evolved together and in tandem. I knew it was something I wanted to study, and there were some people who understood it. I quickly learned that the biology department was focused on other types of research, but the Earth sciences department got it, and I was lucky to find some amazing professors – Sam Bowring and Roger Summons, among others –who were interested in studying just this kind of thing.

While I was an undergrad, I did two summer internships at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and I just loved the idea of exploration. I loved the idea of not just understanding this planet, but trying to understand other planets, and other environments where life may have arisen, by studying the life on this planet and then trying to go out into the solar system, and beyond, and actually study those places themselves.

I stayed at the same school for my Ph.D. that I attended for my undergrad, and after that I did a research postdoc to try to decide whether or not a job in academia was for me. At a poster session at a small conference, I met Mary Voytek, who is NASA’s senior scientist for astrobiology. I basically said to her, "Look, I don't think research or being a professor is for me. What is your job at NASA Headquarters like?” She told me about another postdoc opportunity – this time in management – and I applied for it, and I got it. So, I jumped into my NASA career as a postdoc at NASA Headquarters, and getting that kind of 30,000-foot view showed me how many moving pieces there are (even in just NASA's Planetary Science Division), and how they all work together. That perspective was really my start in the space program and at NASA.

My job has two parts to it. One role is basically as a program officer – I am the lead program officer for NASA’s Exobiology program, which is a research funding program. NASA has a budget that goes to paying scientists who are at other national centers, universities or private institutions to do research that's relevant to our mission at NASA.The Exobiology program is trying to understand the origin and evolution of life on this planet as a way to understand life elsewhere. As a program officer, I'm in charge of managing the budget, looking at new proposals for research in the overall program, and making sure that each of the projects that we do have is making progress toward its goals.

I'm on a couple of our other research funding programs, as well. One is called Habitable Worlds, and it is sort of the flip side to the Exobiology program – focusing on understanding habitability. I also work on a pair of research programs for early career researchers: one for graduate student research and the other, the Early Career Award Program, for people who have their doctorates and are in their first professional positions and are looking for some additional funding.

The other role is my job as the deputy program scientist for astrobiology. In that role I get to wear a lot of different hats. Astrobiology is the study of the origin, evolution, and distribution of life on this planet and throughout the universe. So, the Astrobiology program involves some research funding, but it also involves keeping up with the astrobiology community – which is a broadly defined group from a range of places. It consists of scientists, who perform fundamental astrobiology research, engineers, who think about missions and instruments to look for habitable environments and life, and folks from other disciplines who help us think about the context of these big questions.

In my role as the deputy program scientist for astrobiology, I am in charge of helping the senior scientist think about supporting the community, which can take the form of research funds, but can also take the form of community engagement events – bringing groups in the community together to do collaborative research.For example, it turns out that if you want to think about using a big telescope to look for life on a planet around another star, you have to have some idea of what the signals are – in other words, what does life do on this planet and how could you detect that?. So, you have to have conversations between biologists, geologists, atmospheric chemists and the astronomers who actually look at the signals that come from the telescopes ().The big questions in Astrobiology require scientists from a lot of different fields to address them, and it winds up being a very broad community with a lot of very different types of people.

Talk to everybody you can about how they got to where they are, what their day-to-day work is like, what they love about their jobs, and what they don't like. It's remarkable what you'll find out about what opportunities there are. I have had a career path that is not totally typical, and it was only by talking to people about their jobs that I found something that really fit what I like to do.

I have found that it's easy, since everyone comes up in the academic world, to get a narrow view and think that academia is the only place to be a scientist. It took me a long time to realize there are a lot of different ways to be a scientist – that there are a lot more people involved in this business of science and engineering and space exploration than just people who work in labs. There are a lot of different jobs at NASA, for example, and a lot of different jobs in the field of science that play to different people's strengths.

I have to give credit for getting me on this path to my high school biology teacher, Dr. Lisa Raiford.

I was not a great student in elementary school. In middle school I really started to find my place in my classes and I found things that were more interesting to me, and I started to learn how to focus on what I wanted to do. But it wasn't really until high school that I realized how much I really loved the sciences, specifically biology;understanding the complexity of life on this planet, and the multitude of ways life has evolved to take up the different niches that it does. Dr. Raiford got her Ph.D. while she was teaching high school biology! And she was a really great teacher. Her classes were interesting and very fun. She was a fantastic inspiration for me.

When I first started as a postdoc at NASA Headquarters, I got to work on, and then ultimately became the editor-in-chief for, a document called the NASA Astrobiology Strategy. It was a fantastic opportunity.

Mary Voytek and one of the discipline scientists for astrobiology, Michael New, started the process of rewriting NASA's astrobiology roadmap. It used to be 15 to 30 pages long, buttheir idea was to make this a more ground-up, grassroots document. They started a process by which they polled the community – and ultimately we got a bunch of people from different backgrounds, and at different career stages and with different perspectives on the future and involved them at a bunch of different levels and at different points in the process. What we were trying to reflect was to answer “what is the community going to be doing and thinking about in 10 years?”

Like I mentioned before, the astrobiology community is huge, and involves a lot of people who don't think of themselves as full-time astrobiologists. Many think of themselves primarily as something else – a biologist, a chemist, an astronomer – but also have an interest in astrobiology. In order to write a roadmap for a community that's so diverse, it was important that as many people as possible got a voice and that everybody had a place where they could see themselves in the final strategy.

So, being involved in getting this document written, edited and revised, and incorporating figures and ideas, was great. I got to work with something like 80 to 100 contributors across the field, and the document wound up being around 200 pages.It's just a huge document, but it's really all-encompassing, really broad. It really gives you the sense that astrobiology is a program that involves a lot of people and it's not anything that any one person can do on their own. It is necessarily collaborative, and I think that's really cool. Being involved in that project gave me a sense of the scope of the field, and the research. It was a wonderful project to work on.

I'm from Jupiter, Florida, which is a great place to be from if you're interested in space and space exploration. Jupiter is a few hours south of Kennedy Space Center, which means that when I was growing up, you could see space shuttle launches. If it was dark out, you could see the light from the engines. If it was light out, you'd often see the exhaust trail as astronauts were launched into space. So that was just a very cool thing about growing up there – you were reminded regularly that there were people going into space – or in space! – at that very moment.

In addition to my background in science, I got a minor in literature because it was nice to be able to read some Jane Austen, for example, as part of my work as an undergrad, and to just think about the world in a very different way. I really enjoyed it, even though it didn’t help with the required workload for my major!

I love to travel. At this point, I've been to all the continents except Antarctica and Africa, and those are certainly on my soon-to-visit list.

I love hiking. I have two kids under the age of 5 and we try to go – along with my husband – on weekly hikes. Being outside is certainly one of my favorite things.

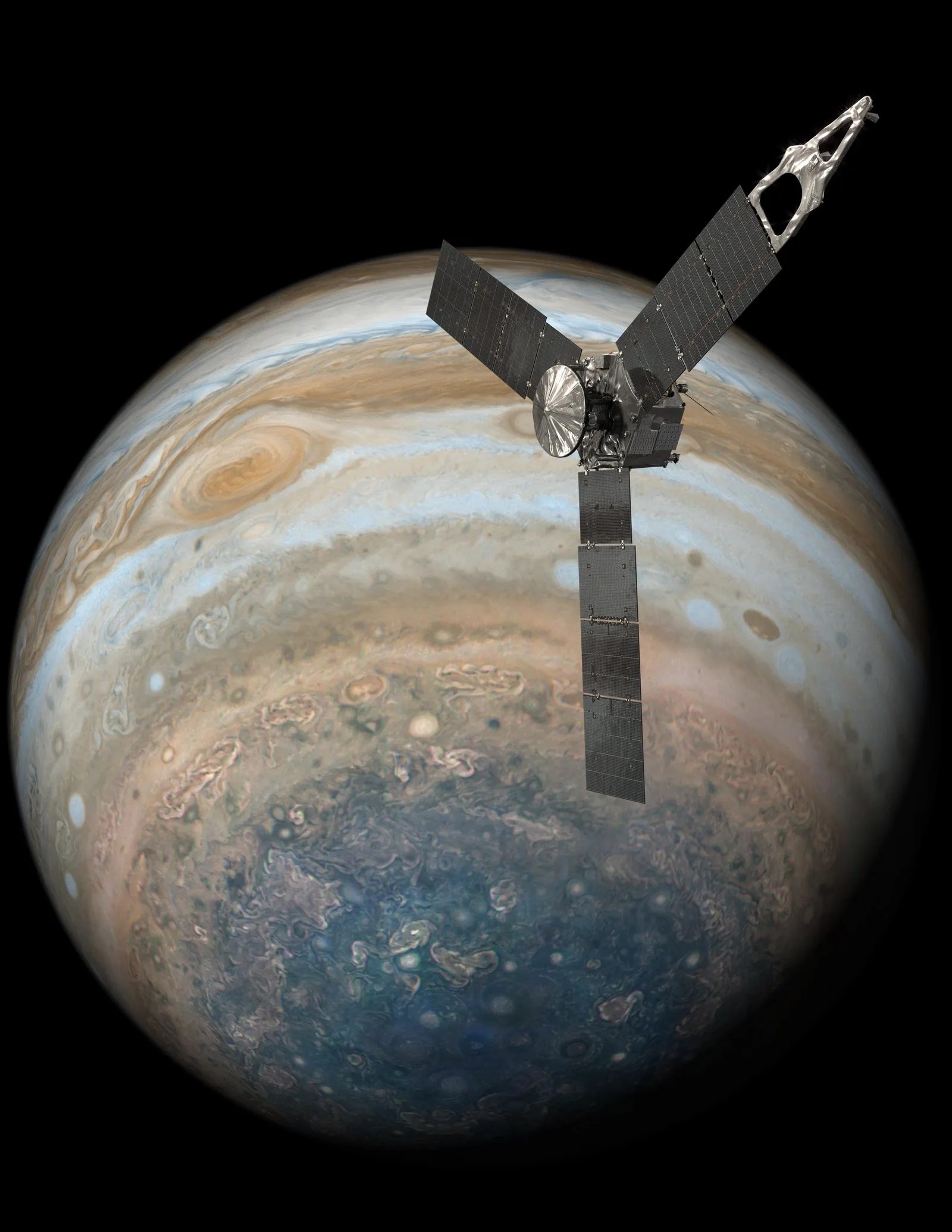

I love the images from NASA’s Juno mission for a number of reasons. First, because most of them are assembled by citizen scientists, which I think is a great reminder