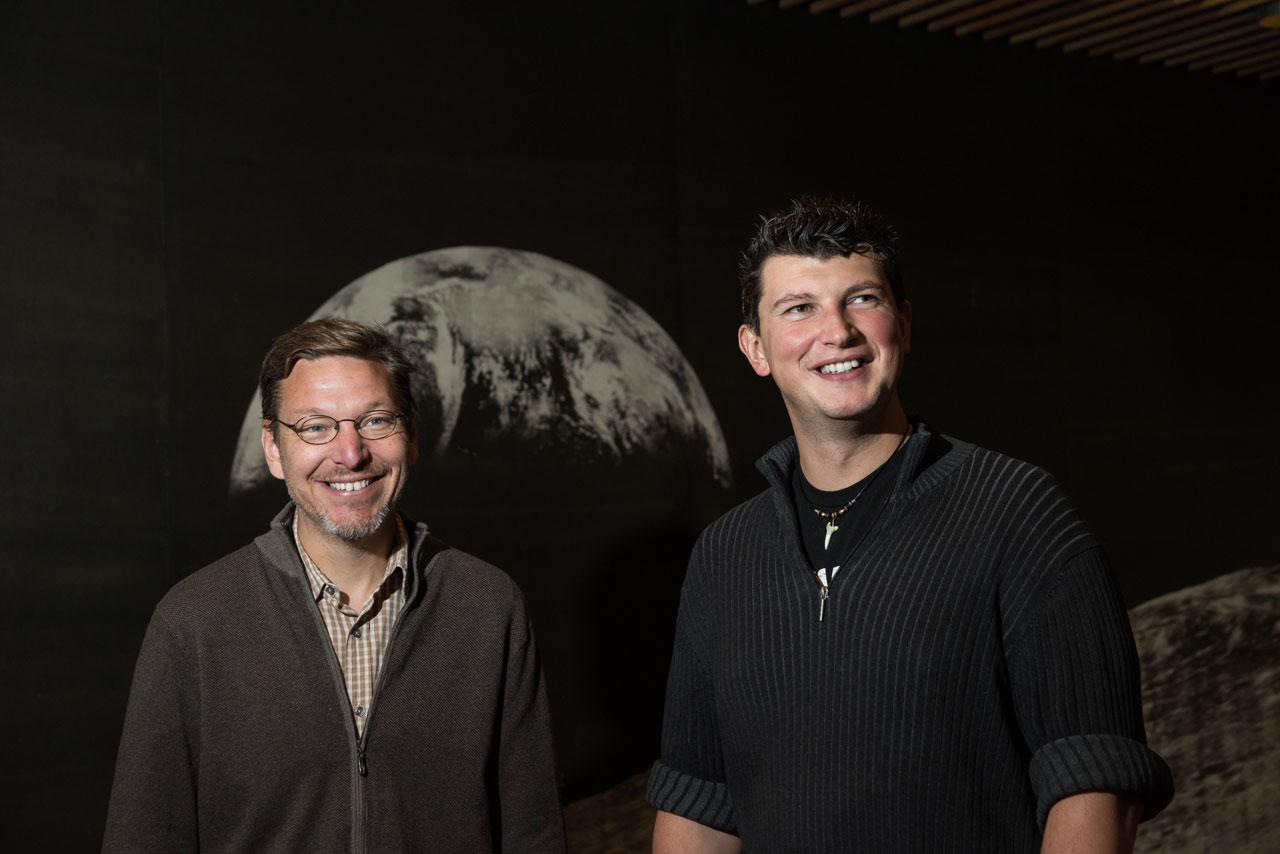

Mike Brown

Astronomer - Caltech

Caltech planetary astronomer Mike Brown is searching for the hypothetical Planet X, which might be orbiting the Sun 100 times farther out than Pluto (or even farther). Here Brown talks about growing up in an Apollo rocket town, realizing astronomy was a legitimate career, the importance of loving what you do and, of course, Planet X (sometimes called Planet 9).

I grew up in Huntsville, Alabama, where they built the Apollo rockets. My father worked on them. When I was there in the early 1970s, pretty much everybody’s father worked on something to do with the space program. You’d walk outside and hear this rumbling — it was a Saturn V rocket on the big tie-down station where they’d test-fire them. It was definitely a spacey place to grow up.

I went to Grissom High School, named after the Apollo I astronaut. We had schools named after astronauts who died. Again, big space town. Alabama public schools are not probably rated the highest in the country, but this little enclave of mostly kids of engineers and things like that was great. Our math team won the national championship many years in a row. When you’re growing up there, you think this is the normal world, but it’s not the normal world.

I liked physics because you could calculate levers and pulleys and mechanical advantage, and I thought that’s what physicists did all day long. I thought it was kind of awesome, so I decided to be a physicist and understand pulleys. I went to the library to look up who had the best physics program and there was this place called Princeton that I had never heard of. So I applied and I got in. I had no idea what I was doing. This is what you could have done a few decades ago just being some slightly smart, dorky kid from Alabama applying out of the blue. I hope it does still happen, but I fear that it doesn’t anymore.

Not only did my father work in the space program, but also I was in kindergarten when man first walked on the Moon. I was in elementary school through the Apollo program, and in a town where they built the Saturn V rocket. My dad worked on the lunar rover buggy. How could I not be interested in space? I say that, but not every kid who grew up there at that time went off and did anything to do with space, so I think something more just stuck in my case. Second grade was the first time anyone asked me what I wanted to be, and I said I wanted to be an astronomer. Things come and go, but I always came back to wanting to understand what’s up in the sky.

I had a great experience at Princeton. I majored in physics because that seemed like a real thing that you can do because people will pay you to calculate pulleys and levers. But there were a few required research projects, and after the first one (on some solid-state particle physics stuff I don’t even remember anymore), the next two I did were in astronomy. I just really wanted to do astronomy but I didn’t think it was practical.

When I decided that I was going to go to graduate school, I chose physics because, again, it’s a real job. I asked one of my professors, the famous physicist-cosmologist Jim Peebles, for a letter of recommendation. “Why are you going into physics?” he said. “You’re really good at astronomy and we need more good astronomers.” And that was it. It was like one person had given me permission to do what I had wanted to do all along, and then all of my graduate school applications were in astronomy, which is just a ridiculous thing to do. How impractical! I’m going to get a Ph.D. in astronomy? That’s crazy!

Every day is potentially different. I can have a day preparing a lecture, teaching in the afternoon and working with students. I can have a day that’s (instead) a night and I am off at a telescope — 14 hours on a mountain summit every night, and desperate attempts to sleep during the day. It’s exhilarating and exhausting. Other days I’m continuing to develop and refine algorithms to help me identify Planet 9 in many different data sets. It’s math and geometry and testing code and finding bugs and all that stuff. Some days I fly across the country and give a talk at some planetarium about Planet 9. Who knows what I’m doing on any particular day. But I need that variety.

I feel like the best advice is make sure you’re going to love what you’re doing. Some amateur astronomers love going out with their telescopes and looking at the sky. But if they went and learned the detailed science and the calculations that a professional astronomer does, it might take the enjoyment out of it. I’m the opposite. I like the detailed science and the calculations and learning how it all works. Well I guess I’m not the opposite because I also love looking at the sky. I just spend far more time sitting in front of my computer — writing code, running code and testing code — than I ever do at a telescope. And I love that.

Also, once you’re an undergraduate, get some research experience. I think astronomy is particularly good for undergrads to get involved in and have a bit more independence. It’s not like a big chemistry lab or biology lab, or something where you’re just a pair of hands carrying out some task that has been predefined by someone else. There’s a lot of astronomy data out there that you can get your hands on and do your own thing with and learn something that nobody’s learned before. I didn’t realize that when I started in astronomy. It’s fantastic.

It’s all hard and challenging. There are moments when you think, “This is just too hard and I can’t do it,” and you power through and blah blah blah. You push until you get to that steady level of challenging and then you just keep going. When it gets easy, you push through that patch quickly and you’re back to where it’s challenging again. It’s never not challenging. If it’s boring, you start doing something more challenging.

I read a lot. I read no science books. I don’t read science fiction, except peripherally. I love good, modern fiction. That’s what inspires me. If I weren’t looking for a planet all day or teaching, I’d be sitting on my couch reading good, modern fiction all day. I go through phases. At the beginning of 2018, I realized that I have disproportionately not read many novels by women and underrepresented minorities, so my project for 2018 was to read more of those novels and it was fabulous. I read things I would never have just randomly picked up, and they’re different and interesting and inspirational.

Planet 9 is the highlight of my career. Most of the stuff I’ve done in the past has been more solitary, or me with my students as opposed to another equal-level person. So it’s been fun having a back and forth with Konstantin Batygin all the time. I’ve learned so much from him and I think he’d say the same thing. I wouldn’t have been able to get there myself, and I don’t think he would have either. We both understand a lot more about the solar system than when we started. This has been as good as it gets. It’s exhilarating! it’s terrifying! I go through stages where I’m semi-convinced we won’t find it and I’m suddenly depressed and mopey, and the next day I’ll say, “No! We’re going to find it!” And then I’ll be excited.

It is really hard for me to imagine what’s going on in the outer solar system if there’s not a planet out there. But just because it’s hard for me to imagine doesn’t mean it’s not true. Maybe there’s something really weird going on that we haven’t thought of. The easiest explanation is a planet. Who knows? With luck we should find out soon.

Planetary science is a global profession.