Kate Marvel

Associate research scientist - Columbia University / NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies (GISS)

Upper Arlington High School, Ohio

BA from UC Berkeley, PhD from the University of Cambridge

Double majored in physics and astronomy, PhD in theoretical physics

I never thought I was going to be a scientist. I went to college and thought I was going to major in English and drama and then try to become an actress. I took “Introduction to Astronomy” as a distribution requirement in college. I remember sitting there and thinking, “This is amazing! Why didn’t anyone tell me this was amazing?” I thought it was so cool and wanted to know more, so I switched my major.

After I got my PhD, I knew I didn’t want to do theoretical physics (string theory, string cosmology) anymore, but I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do. Then I found climate science, which is perfect because it’s a lot of physics, computer programming and data analysis. It’s something that people care about. It’s something that I think really has relevance.

I love my job because I get to study the best place in the universe. I use satellite observations of the climate system, reconstructions of past climate change, and the output of computer models of the climate to understand what is climate change actually like, and is it happening now?

It’s great because I get to work with so much data!

I’m not sure I’m the best source of career advice! But I would say that a lot of people think they have to be a genius to work in physics, and that is not true at all.

I get really annoyed when people tell me they’re bad at math, because I don’t think anyone is “bad” at math. I think it’s hard, but it’s hard for everybody. If you don’t understand something, it doesn’t mean you’re intrinsically bad at it. It means you have to find another way around it, another way of understanding it. So, you’re not bad at math, and you’re not bad at physics.

I would say switching into a totally new field. I didn’t have a background in Earth science at all, but I had the raw tools of physics and math. I have these problem-solving skills, and I knew how to program, but I didn’t know anything about this world that I wanted to study. That was really challenging, but I just asked a lot of really stupid questions to a lot of really patient people, and they were amazing. They were so generous with their time and so patient with my dumb questions. That’s how I learned, and I’m totally grateful for them.

My colleagues. You know, there are so many brilliant and great people who work in climate science. So, I’m inspired by people who are scientists, like Kim Cobb and Katherine Hayhoe, and people who work in policy, like Rhiana Gunn-Wright, who’s doing work for the Green New Deal. Like Katherine Wilkinson, who’s the VP for Project Drawdown, who’s phenomenal. Ayana Johnson, who runs Ocean Collectiv and is a marine biologist and really good at advancing this argument that ocean conservation and climate change are civil rights issues.

So, I feel like, within the space of climate (broadly defined), there are so many phenomenal, brilliant and kind women, and I love it.

The project that I just finished, that happened because the guy at the office next door to me is a drought researcher who works a lot with tree ring data. I just wandered into his office and was like, “Ben, explain tree rings to me. Does it hurt the trees? Like, what do you do?” And we started working together. We got this result that humans have been affecting global drought as early as the first half of the 20th century.

I feel like there should be an untranslatable German word for that feeling, where you figure something out and you’re really excited about it, but then you’re like, “Oh my god, the implications of what I figured out are really horrifying!” That was an amazing project to work on because it combined some of my statistical techniques with some of his expertise in tree rings. It was such an awesome project to work on, and I learned so much.

My last name is really Marvel. I used to teach in prison. At San Quentin State Prison, I taught statistics and algebra, and they were the best students I ever had. I have a dog named Arthur Canine Doyle, and I’m really proud of that.

I like to read. I like to write. I have a small child, so most of my hobbies are small-child-centric.

Most of my research is modeling, so I don’t get to do exciting field work. When I was in graduate school, I went to a physics conference in Tehran, Iran. There are so many parallels between Tehran and Los Angeles. It’s basically the same city—the crazy car culture, the mountains, and the smog. It’s beautiful, though.

All of my good stories are stories that actually happened to one of my friends that I steal and pretend happened to me.

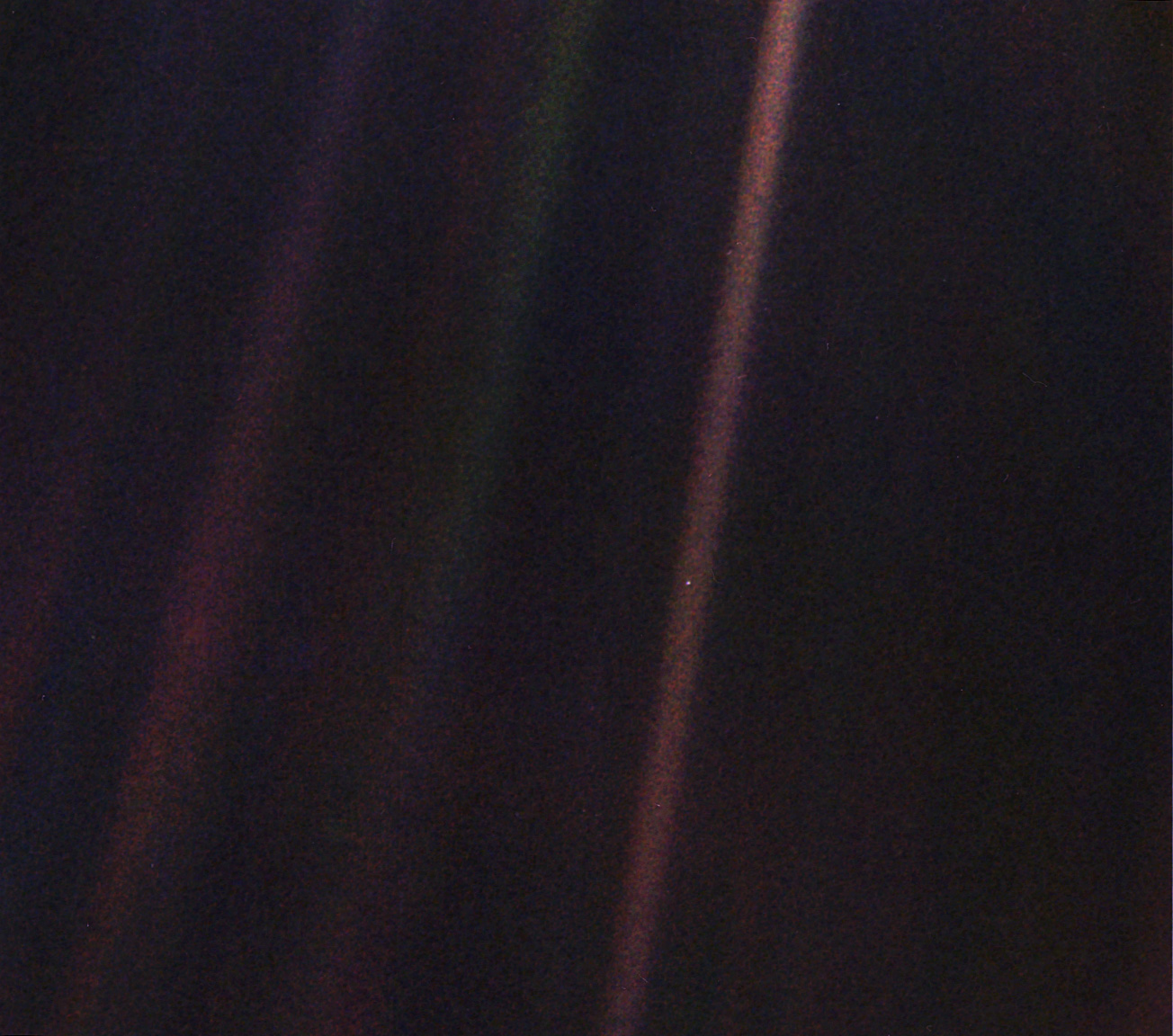

My favorite space image is probably the “Pale Blue Dot,” because it just encapsulates why I do what I do. That’s us. Everybody I care about is there, and that’s so important.

Planetary science is a global profession.