Konstantin Batygin

Associate Professor of Planetary Science - Caltech

University of California, Santa Cruz

A skateboarding enthusiast and hard rock guitarist, Konstantin Batygin is a researcher and associate professor in planetary science at the California Institute of Technology. Read on to learn about the search for the hypothetical Planet 9, the importance of mentorship and curiosity in research, and the importance of being comfortable with failure.

I’m originally from Moscow, Russia. I was born there in 1986. Then we moved to Japan in 1994, and to the U.S. in 1999 in the middle of my eighth-grade year.

I went to high school in San Jose, California. I had a great high school experience. I wasn’t a super-dedicated student, but I did realize in high school that I was pretty good at physics and math. I genuinely just enjoyed it. I also played in a band — we played a bunch of shows. I’ve been playing music since my family moved to the U.S. and I’m still in the same band that I started in late high school.

I went to college at the University of California, Santa Cruz. I initially got accepted into college as an engineering major or an engineering/physics major — I don’t really remember. But on the first day, I changed my major to astrophysics. This was all Plan B anyway, because my band was going to become the next Metallica. (By the way, we still are. We’re four shows away right now from making it big. I can feel it. Four more shows at the Old Towne Pub in Pasadena, and we’ve made it. After that, world tour.)

We mostly play stuff that I wrote, mostly in A minor. I don’t even understand why there are other chords. It’s the only chord — the only one I know. (I’m joking of course.) We also make metal renditions of 60s rock ‘n roll. One of my favorite cover songs to play is “Roadhouse Blues” by The Doors because it’s a metal song. It’s a metal song before metal was fully conceptualized. I love playing that song live because it just brings the room’s energy level to infinity.

At a party in the beginning of my sophomore year, I met Greg Laughlin, an astrophysics professor at UC Santa Cruz. He told me that astrophysicists still didn’t know the long-term fate of the solar system, as in whether it’s stable. “What do you mean?” I said, “Of course it’s stable. It’s here. We live in it.” But he said it’s an unsolved problem. I just couldn’t believe that there were still simple problems — obvious questions that were unsolved. I think the common perception is that to do any kind of scientific research, you have to do something that is at the cutting edge and super complicated. But the truth is that some of the most insightful, interesting and fundamental questions are some of the simplest ones you can ask, like why is Jupiter’s Great Red Spot red? We still don’t know.

So I asked Greg if I could solve the problem of the solar system’s stability. As in, would he help me solve the problem. He invited me to visit his office the next day. I was nervous because I thought he was going to give me some test, like ask me to solve problems on the board. But I showed up and he said, “get set up and start solving the problem.” He gave me a paper written by a French scientist and said, “Read this and start thinking about the long-term fate of the solar system.” That’s how I got started in research. I didn’t have to pass a test. I just showed up. Greg and I remain very close friends to this day. He’s fantastic. I owe a lot to him. And by just meeting him and asking him some questions, I got involved in research.

It was really difficult at first. I made every possible mistake that I could make. But that’s actually what research is. Success is built on layers and layers of failure. What’s astonishing is that after two and a half years of working on this problem, I actually did solve it. I demonstrated that Mercury could get ejected from the solar system before the Sun enters its red giant phase and absorbs the inner solar system. There’s a one percent chance that this will happen over the next 5 billion years. The inner solar system could undergo a large-scale dynamical instability and just fall apart. Mercury’s orbital eccentricity can reach extremely high values until it starts having close encounters with Venus and Earth, and then if Mercury’s semi-major axis starts to even flirt with that of Jupiter, then Jupiter ejects Mercury from the solar system.

At Caltech, we professors teach a couple classes per year. It’s a small enough teaching load that you can do a really good job. A huge and important part of the job is mentoring undergrads and grad students — making sure they’re doing interesting research and providing help and advice along the way. The rest of the time, what I do 100 percent is follow my curiosity (not the Mars rover, but my own curiosity). My work as a theorist is predominantly aimed at discovering new things and understanding how the solar system and other planetary systems work.

There are infinite problems out there, but finding the right problem — something that’s important and that’s potentially going to lead to a profound answer — is half of the challenge. And actually having in some sense (I don’t like using this word) but having the courage to pursue it. I genuinely try to pursue things that have a high probability of failure. And you know what? Ninety-nine percent of the ideas I try just don’t work out. I work out the math, I do computer experiments, and I then realize this was a terrible idea and I should have realized it was a terrible idea before I started. The upshot is that oftentimes when you realize it was a terrible idea, a new idea comes along from that realization.

Definitely Planet 9. It is an awesome one to work on. It’s rare for there to be a ready-to-go observational test for your theory. General Relativity is a great example. Einstein predicted gravitational waves in 1916, and we didn’t observe them until 2015. But Planet 9 is in a different category. Mike Brown and I wrote a paper back in 2016, and we both wrote a couple of papers since, all of which built together this picture that is readily testable. You go out to a telescope and you search the night sky, and Planet 9 is either there or it’s not. That theory has a resolution point, and it’s not 100 years away — it’s a decade. The thrill of that is hard to describe, really.

Science is not something that you just do by yourself in a room because you’re trying to solve something for a higher cause. It has to be fun. It’s really important who we do it with. Especially at early stages, we need mentorship. Very few people will just become amazing physicists or astronomers or biologists just by thinking about stuff and figuring it out. You need to go through the process of having a mentor, or multiple mentors, who can show you how to do it. The most important advice that I can give is make sure that your mentors are just the best people. The only reason I’ve made any progress ever, is because of the mentors that I had all throughout my career.

I’m quite inspired by my academic advisors. All of them. I hold all of them in very high regard. Of course, my parents. I also love to read about the history of astronomy. I find inspiration in realizing that some of the scientists who have a god-like presence in textbooks were really just flawed people like everybody else. That’s inspiring because once you realize that everybody is just a person, it lowers the barrier to try new things. I also professionally get really inspired listening to the Beatles. It’s the dumbest thing, but it’s true. If I’m out of ideas, I usually listen to the Beatles and I think about space and stuff. It allows my brain to wander more. That’s actually really important for a scientist — taking the time to sit around and imagine stuff, and be curious.

I’ve been doing martial arts since I was eight. I love to spar. Doing training and martial arts is the best way I’ve found to keep myself centered. Having an outlet is a good thing. Also I skateboard all around campus. My favorite hobbies are skating, surfing, snowboarding and stuff, but mostly l like playing music and writing music, and I try to stay pretty active. If I don’t, I start to get weird and frustrated. A good way to maintain sanity is to make sure you’re not staying still.

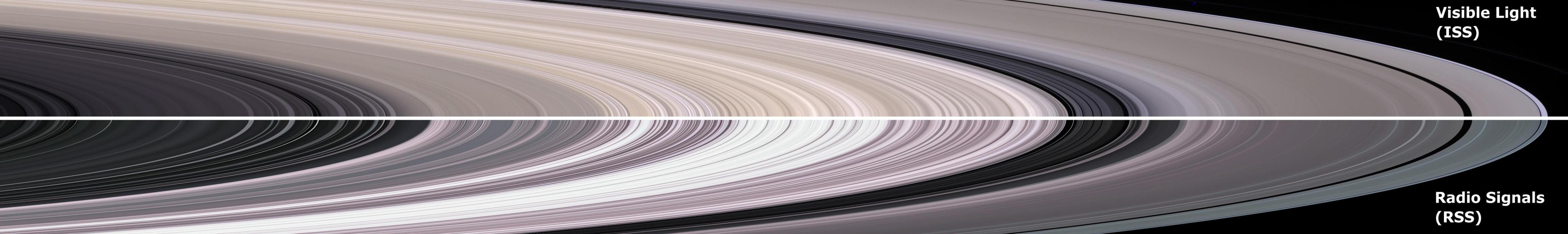

The Cassini image of Saturn’s rings in radio and visible light. The reason it’s beautiful is that it looks like sand that a cat took and brushed with its claws. If you look at the beautiful fine structure, you can obsess over this for months because it is so cool. Nature is like “because this is too complicated, I’m going to show you a picture."

Caltech researchers have found mathematical evidence suggesting there may be a "Planet X" deep in the solar system. This hypothetical Neptune-sized planet orbits our Sun in a highly elongated orbit far beyond Pluto. The announcement does not mean there is a new planet in our solar system. The existence of this distant world is only theoretical at this point and no direct observation of the object nicknamed "Planet 9" have been made.

Planetary science is a global profession.