Michele Dougherty

Principal Investigator, Magnetometer Instrument, Cassini Mission - Professor, Imperial College in London

I was born in South Africa and I lived there until I finished my Ph.D. I loved living in South Africa. I love big open spaces and blue skies. But South Africa doesn't really focus on space science, and that is one of the reasons I moved to Europe. I am now living in London. I enjoy living in London, but the weather can be very dreary; I find winters particularly difficult. However, I do live in a really nice part of London, which is close to a park and near the river.

It was when I was a young child – I must have been 10 or 11 years old when my dad built his own 10-inch telescope. He ground the mirror, and my sister and I helped mix the concrete for the base of the telescope. When my dad finished putting it together I remember looking through it and viewing the moons of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn. I was so excited to see these objects, of course not knowing that in the future I would be involved with a space mission orbiting around Saturn.

It was actually a rather roundabout route. I got my Ph.D. and was trained as an applied mathematician in South Africa. When I left South Africa I went to Germany for a couple of years on a fellowship and I worked mainly in applied mathematics. After that, I wanted to move to an English-speaking country, and so I went to work for the Imperial College in London. After I had been there for six months I was asked by the person I was working for whether I would like to get involved with preparing a magnetic field model for when the Ulysses spacecraft flew past Jupiter on its way to orbit the Sun at its poles. I thought that this was a good thing to do, so I began to work on that, but slowly and surely it took up all of my time. It has now been my focus since 1991.

My dad. I think he was my first inspiration. As a young girl growing up, my dad instilled into me that I could do anything I wanted to do. I never stopped to think that because I was a woman I shouldn't be doing physics.

I've worked with some really good scientists who have also helped to inspire me. Margy Kivelson, who is based at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), was one of the high-profile woman scientists that I have met in the United States. Seeing how well she had done, and how far she had come made me realize that I could achieve my goals too.

I am a professor of space physics at the Imperial College in London. I was the Principal Investigator (PI) for the magnetometer instrument on NASA's Cassini spacecraft. In that role, I was responsible for managing a team of about 40 scientists, and an operations team as well, to make sure we did good science with the data from this instrument.

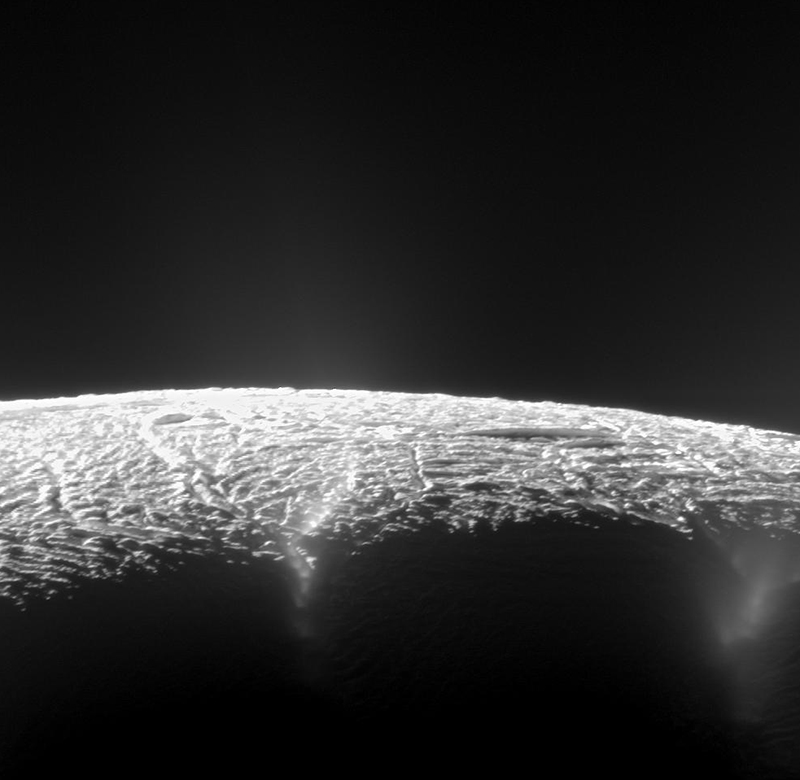

My favorite moment is linked with Cassini. In a distant flyby of Saturn's little moon called Enceladus the instrument I was responsible for measured some rather strange signatures in the data. We weren't quite sure what we were seeing, but we did a bit of work on it, and what we thought we were seeing was an atmosphere. (If you have an atmosphere around a body the magnetic field signatures that you see take on a particular shape.) That was a great surprise. So I let the Cassini team know that there was something really interesting going on at Enceladus and I persuaded them to take the spacecraft really close in on one of the subsequent flybys of this moon.

I must confess before that flyby took place, I had a few sleepless nights. (I was concerned that maybe we had misinterpreted the data.) So, my favorite moment occurred when we realized that yes, there WAS this rather strange atmosphere with plumes of water vapor coming off of Enceladus.

Have confidence in yourself. Don't be put off by minor hurdles you might come up against. Be prepared to change direction if something interesting is put before you. If I had been less brave when I was asked if I wanted work on space physics problems then I wouldn't have had all the fun I've had for the last 20 years.

I go for long walks in the park with friends and family. I swim, and I read. I enjoy watching wildlife, and so I tend to choose holidays where I can take photographs and videos of wildlife. Every so often it is really important to get away from the work that you do everyday, to recharge your batteries and gain your enthusiasm back again.

Persevere. As a student at an all-girls school in South Africa, I didn't do physics or chemistry – they didn't offer these classes. While in college, I decided to take physics my first year – that was probably the hardest year I have ever had. I would sit in on lectures and everyone else seemed to know what was going on. I didn't have a clue, but I persevered. You just need to persevere. There will be times when you don't think you are doing the right thing, but don't make any hasty decisions. Just hang on in there and you just might surprise yourself.

Planetary science is a global profession.