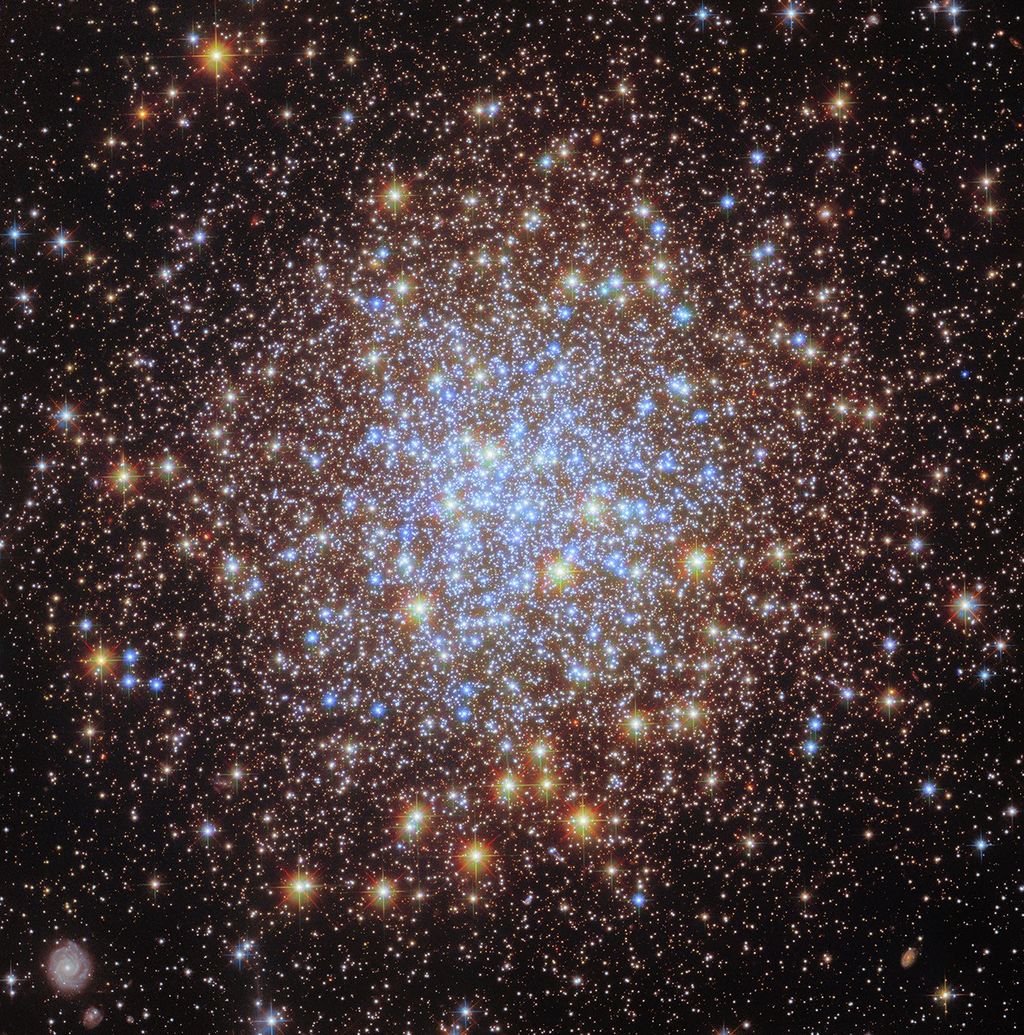

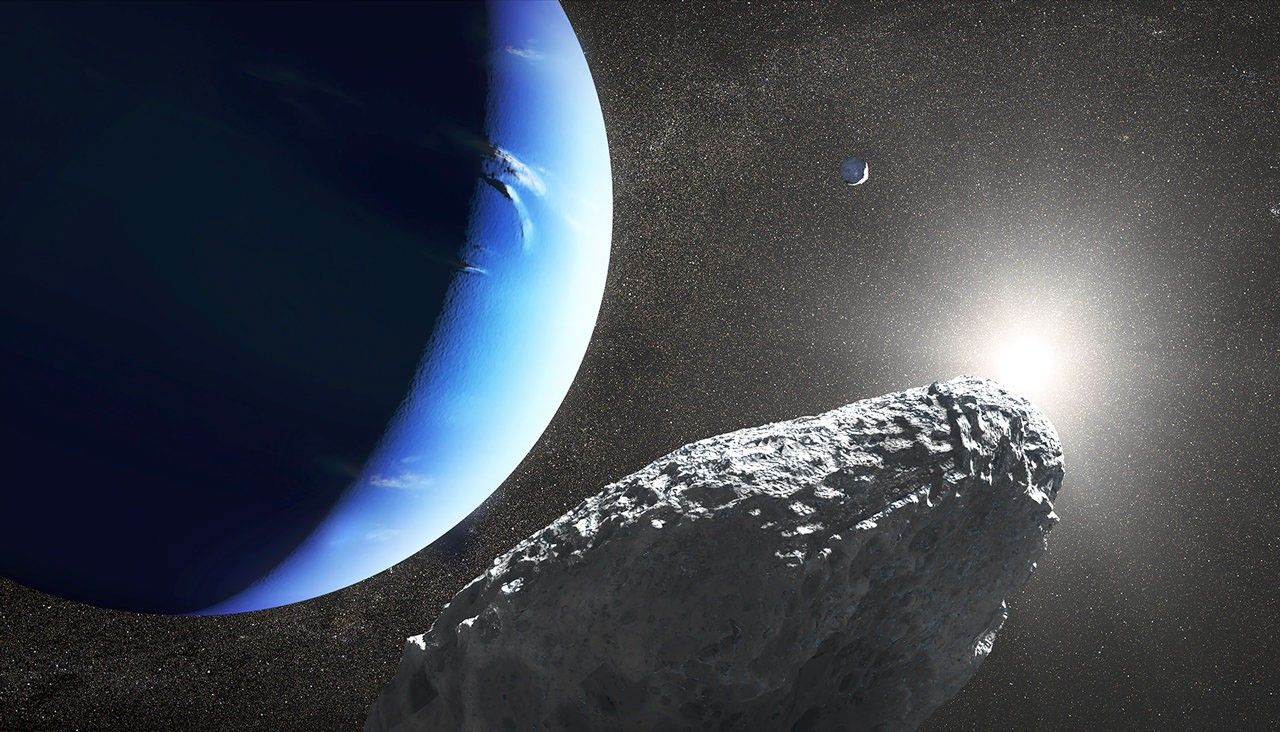

Scientists may have an explanation for a mysterious moon around Neptune that they discovered with Hubble in 2013.

Astronomers call it "the moon that shouldn't be there."

After several years of analysis, a team of planetary scientists using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope has at last come up with an explanation for a mysterious moon around Neptune that they discovered with Hubble in 2013.

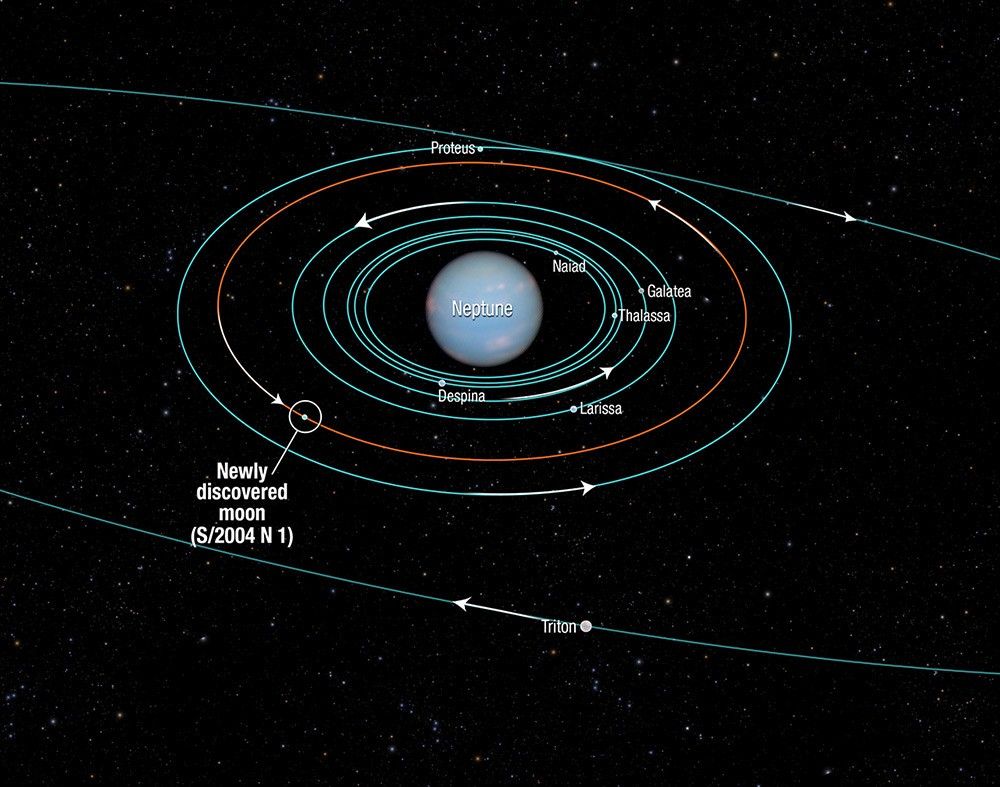

The tiny moon, named Hippocamp, is unusually close to a much larger Neptunian moon called Proteus. Normally, a moon like Proteus should have gravitationally swept aside or swallowed the smaller moon while clearing out its orbital path.

So why does the tiny moon exist? Hippocamp is likely a chipped-off piece of the larger moon that resulted from a collision with a comet billions of years ago. The diminutive moon, only 20 miles (about 34 kilometers) across, is 1/1000th the mass of Proteus (which is 260 miles [about 418 kilometers] across).

"The first thing we realized was that you wouldn't expect to find such a tiny moon right next to Neptune's biggest inner moon," said Mark Showalter of the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California. "In the distant past, given the slow migration outward of the larger moon, Proteus was once where Hippocamp is now."

This scenario is supported by Voyager 2 images from 1989 that show a large impact crater on Proteus, almost large enough to have shattered the moon. "In 1989, we thought the crater was the end of the story," said Showalter. "With Hubble, now we know that a little piece of Proteus got left behind and we see it today as Hippocamp." The orbits of the two moons are now 7,500 miles (about 12,070 kilometers) apart.

Neptune's satellite system has a violent and tortured history. Many billions of years ago, Neptune captured the large moon Triton from the Kuiper Belt, a large region of icy and rocky objects beyond the orbit of Neptune. Triton's gravity would have torn up Neptune's original satellite system. Triton settled into a circular orbit and the debris from shattered Neptunian moons re-coalesced into a second generation of natural satellites. However, comet bombardment continued to tear things up, leading to the birth of Hippocamp, which might be considered a third-generation satellite.

"Based on estimates of comet populations, we know that other moons in the outer solar system have been hit by comets, smashed apart, and re-accreted multiple times," noted Jack Lissauer of NASA's Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley, a coauthor on the new research. "This pair of satellites provides a dramatic illustration that moons are sometimes broken apart by comets."

Hippocamp is a half-horse half-fish from Greek mythology. The scientific name for the seahorse is Hippocampus, also the name of an important part of the human brain. The rules of the International Astronomical Union require that the moons of Neptune are named after Greek and Roman mythology of the undersea world.

The team of astronomers in this study consists of M. Showalter (SETI Institute, Mountain View, California), I. de Pater (University of California, Berkeley, California), J. Lissauer (NASA Ames Research Center, Silicon Valley, California) and R. French (SETI Institute, Mountain View, California).

The paper will appear in the February 21 issue of the science journal Nature.

The Hubble Space Telescope is a project of international cooperation between NASA and ESA (European Space Agency). NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, manages the telescope. The Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, conducts Hubble science operations. STScI is operated for NASA by the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy in Washington, D.C.

Ray Villard

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Maryland

410-338-4514

villard@stsci.edu

Mark Showalter

SETI Institute, Mountain View, California

mshowalter@seti.org

Jack Lissauer

NASA Ames Research Center, Silicon Valley, California

jack.lissauer@nasa.gov