6 min read

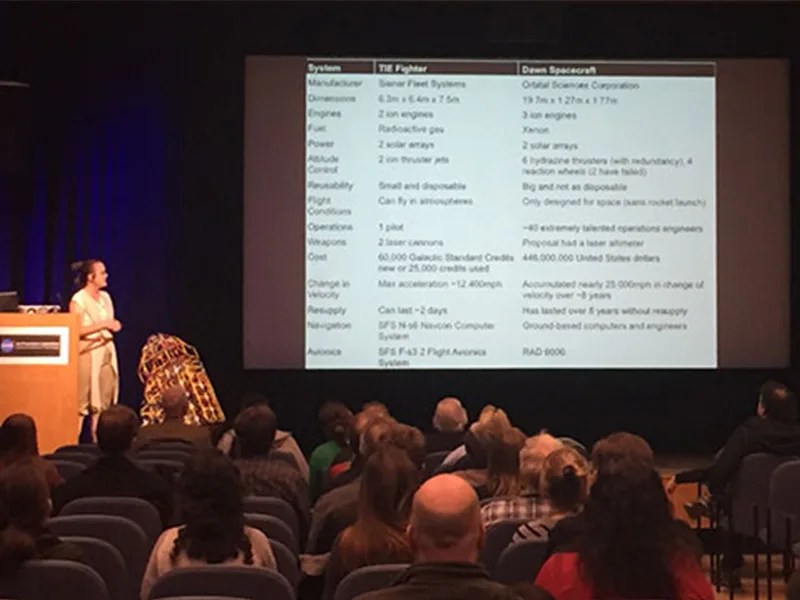

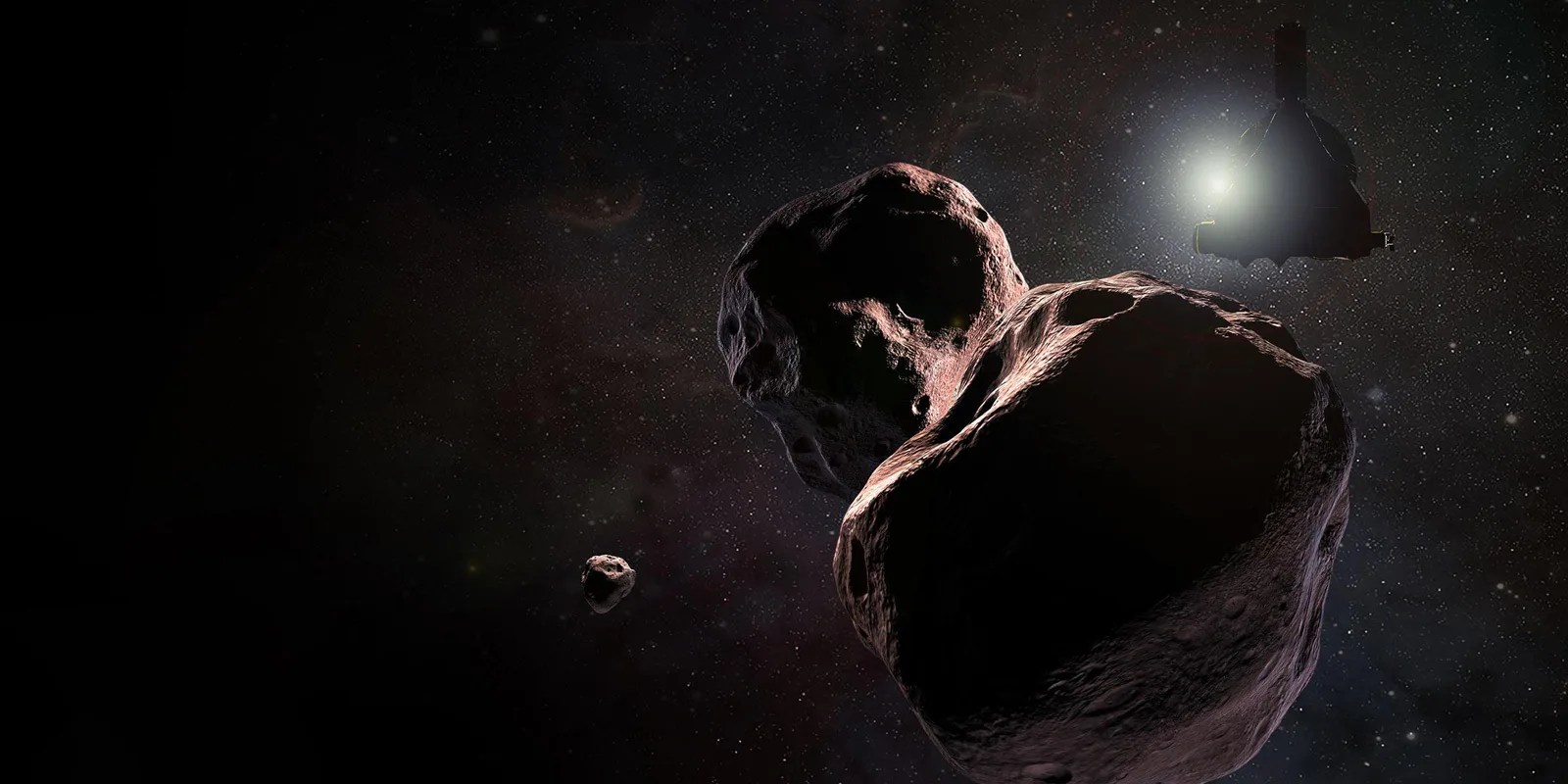

As you walk into Keri’s office, you are immediately greeted by a large display of Star Wars memorabilia. Beside a shelf of books and binders are colorful posters and a vast array of figurines. Rey, the latest trilogy’s daring female protagonist, has her own dedicated shelf. On Keri’s desk, there is a large desktop computer with a bright, color-coded spreadsheet pulled up. She sits a three-hundred-something page stack of code in front of the computer with a light thud. “This,” she says, pointing to the stack before her, “is all of that code for that,” nodding to the computer. As she arranges a full spectrum of highlighters on her desk, she explains that the spreadsheet on the computer is a list of all of the command sequences that will be sent up to NASA’s Dawn spacecraft in around six weeks. Right now her task is to review all of the code for each sequence, checking for errors. In other words, she is making sure Dawn has all of the instructions it needs to take more photos and collect other valuable information about dwarf planet Ceres, which it has been exploring since 2015.

Keri Bean is a science planning and sequencing engineer for Dawn and is training to be a Mars rover driver for the Mars Exploration Rovers (MER). Her job on Dawn is to make sure the spacecraft has a plan to collect the observations of Ceres that the science team needs to meet its scientific goals. Essentially, this involves a lot of communication between the science team and the flight operations team. Much of the sequencing for which she is responsible is planned months to years ahead of time. From the spacecraft’s planned trajectory, she can run programs to predict what might be visible from the spacecraft’s path. If scientists want to study a specific feature in further detail based on new data, the sequencing team does its best to accommodate these requests. The sequencing team must also consider that Dawn’s memory and communication time with Earth is limited. When planning data collection, Keri and her team have to take into account when the spacecraft is communicating with Earth, how long information will take to travel to and from the spacecraft, and how much memory is available until the next downlink (transmission of data to Earth). For example, if Dawn’s memory were mostly full, Keri’s team would have to limit its observations, taking only the most salient data, until Dawn could send back data and unload its memory.

To do this, Keri also helps write the code that tells the spacecraft what to observe and how. There are instrument sequences that direct individual instruments’ observations as well as a background sequence that manages the spacecraft’s communications with Earth. Though instrument teams at other institutions usually write the code for their instruments, Dawn is unique in that the sequencing for one of its instruments, the gamma ray and neutron detector, is done at JPL. After each instruments’ sequences for the next observation cycle, anywhere between a few days and a few months, are coded, Keri sits down to review the code, as she is doing today. After she checks to make sure that each code is error-free and matches the corresponding sequence ID on her computer’s spreadsheet, the sequencing goes for a trial run in the testbed, a room of computers with the same software as the spacecraft where commands may be tested before being sent to the spacecraft. Most missions have dedicated testbed engineers, but with Dawn, like other small missions, many team members do work beyond that described by their title, so Keri gets to conduct some of these tests herself.

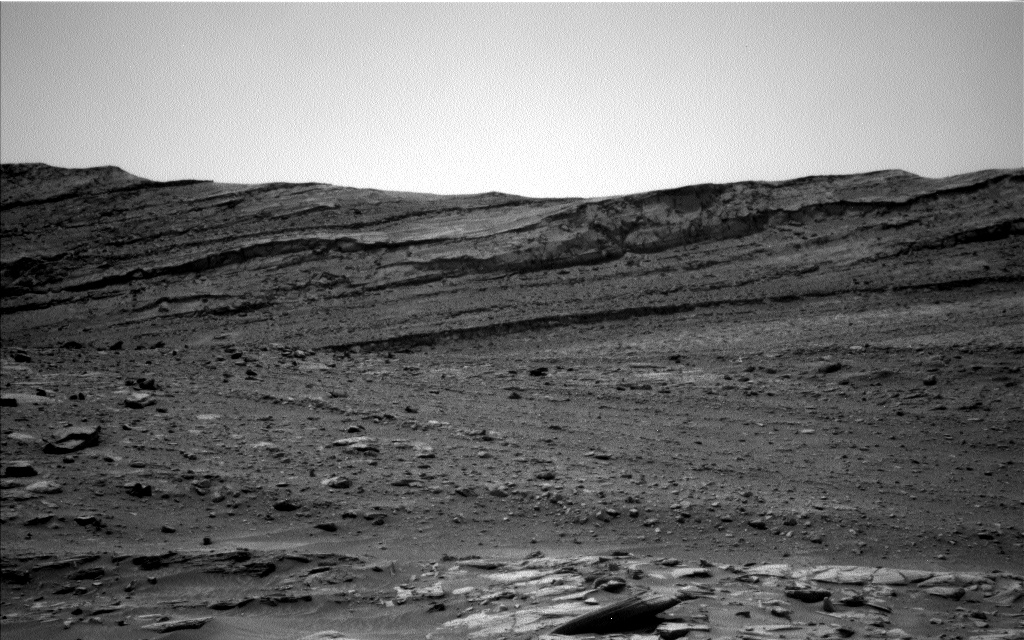

You might wonder how Keri arrived at such a multi-faceted job. During her university years studying meteorology, Keri began working with Phoenix and then Curiosity, both Mars landers, looking at the weather on Mars and helping with mission operations. Offered a job on Dawn, though different from her previous experience with Mars, she chose to pursue the wide range of experience that it would provide her. Though Dawn had new quirks for her to get used to (like the manual sequence review process, complete with a full rainbow of highlighters, as opposed to MER’s more online tool-based process), she says that there was a reassuring sense of familiarity. Though a trained meteorologist, Keri eventually began to pick up on Dawn’s geology-based approach to planetary exploration. After Dawn’s primary mission ended, Keri added on work for MER. Having worked for MER before Dawn, she had a good understanding of its history and noticed how the project had changed since her time there. A lot of knowledge, she says, was lost with time when some of the original engineers left the project. When she rejoined, the fresh perspective she brought from her prior MER work and from Dawn was valuable. She focused on updating and standardizing sequencing team procedures based on what she saw with Dawn. She says that, while she has a strong education in science, much of the knowledge and skills she uses on a day-to-day basis come from her experiences on different missions.

In this way, Keri is representative of a younger generation of JPLers who are somewhat interdisciplinary in their approach to projects. Like her colleagues, one of whom is a graphic designer-turned MER sequencer, her work at JPL spans different jobs, projects, and disciplines, lending a fresh perspective to each new undertaking. Occasionally, this involves questioning established modes of operation and updating them wherever improvements can be made.

Keri believes fervently in the importance of science education and outreach, especially for girls. Early in her graduate career, she attended a dinner following a meeting of Curiosity’s Mast Camera team. Having just started, Keri “hardly knew anyone” there. She found herself next to Dawn Sumner, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Davis, who mentored her throughout the dinner. At the end of the meal, Keri realized that she didn’t have any cash on her. Dawn offered to pay for her and told Keri not to pay her back. Instead, when she was able to do so, Dawn asked that Keri pass the favor forward and mentor other young women in science. “I took that to heart,” she says. “I’ve probably paid that forward a dozen times over now, but it seemed like the least I can do to carry that on.”

Overall, Keri’s passion for each project she works on characterizes her enthusiastic, dedicated approach. This passion extends beyond her work; in her free time she is active on social media, sharing her excitement about science with the world. She’s even built her own functioning, full-size R2D2, applying her engineering skills to her hobbies. So when you leave her office, you know why Rey has her own shelf. Like Rey, Keri is guided by an inherent sense of curiosity and a deep-seated commitment to exploration.