News | January 21, 2015

Gullies on Vesta Suggest Past Water-Mobilized Flows

› Larger image and caption

Protoplanet Vesta, visited by NASA's Dawn spacecraft from 2011 to 2013, was once thought to be completely dry, incapable of retaining water because of the low temperatures and pressures at its surface. However, a new study shows evidence that Vesta may have had short-lived flows of water-mobilized material on its surface, based on data from Dawn.

"Nobody expected to find evidence of water on Vesta. The surface is very cold and there is no atmosphere, so any water on the surface evaporates," said Jennifer Scully, postgraduate researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles. "However, Vesta is proving to be a very interesting and complex planetary body."

The study has broad implications for planetary science.

"These results, and many others from the Dawn mission, show that Vesta is home to many processes that were previously thought to be exclusive to planets," said UCLA's Christopher Russell, principal investigator for the Dawn mission. "We look forward to uncovering even more insights and mysteries when Dawn studies Ceres."

Dawn is currently in the spotlight because it is approaching dwarf planet Ceres, the largest object in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. It will be captured into orbit around Ceres on March 6. Yet data from Dawn's exploration of Vesta continue to capture the interest of the scientific community.

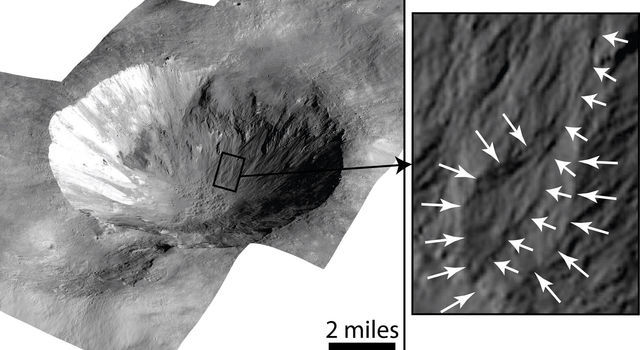

Scully and colleagues, publishing in the journal "Earth and Planetary Science Letters," identified a small number of young craters on Vesta with curved gullies and fan-shaped ("lobate") deposits.

"We're not suggesting that there was a river-like flow of water. We're suggesting a process similar to debris flows, where a small amount of water mobilizes the sandy and rocky particles into a flow," Scully said.

The curved gullies are significantly different from those formed by the flow of purely dry material, scientists said. "These features on Vesta share many characteristics with those formed by debris flows on Earth and Mars," Scully said.

The gullies are fairly narrow, on average about 100 feet (30 meters) wide. The average length of the gullies is a little over half a mile (900 meters). Cornelia Crater, with a width of 9 miles (15 kilometers), contains some of the best examples of the curved gullies and fan-shaped deposits.

The leading theory to explain the source of the curved gullies is that Vesta has small, localized patches of ice in its subsurface. No one knows the origin of this ice, but one possibility is that ice-rich bodies, such as comets, left part of their ice deep in the subsurface following impact. A later impact would form a crater and heat up some of the ice patches, releasing water onto the walls of the crater.

"If present today, the ice would be buried too deeply to be detected by any of Dawn's instruments," Scully said. "However, the craters with curved gullies are associated with pitted terrain, which has been independently suggested as evidence for loss of volatile gases from Vesta." Also, evidence from Dawn's visible and infrared mapping spectrometer and gamma ray and neutron detector indicates that there is hydrated material within some rocks on Vesta's surface, suggesting that Vesta is not entirely dry.

It appears the water mobilized sandy and rocky particles to flow down the crater walls, carving out the gullies and leaving behind the fan-shaped deposits after evaporation. The craters with curvy gullies appear to be less than a few hundred million years old, which is still young compared to Vesta's age of 4.6 billion years.

Laboratory experiments performed at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California, indicate that there could be enough time for curved gullies to form on Vesta before all of the water evaporated. "The sandy and rocky particles in the flow help to slow the rate of evaporation," Scully said.

The Dawn mission to Vesta and Ceres is managed by JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington. UCLA is responsible for overall Dawn mission science.

For more information about Dawn, visit: