Solar System Exploration Stories

Filters

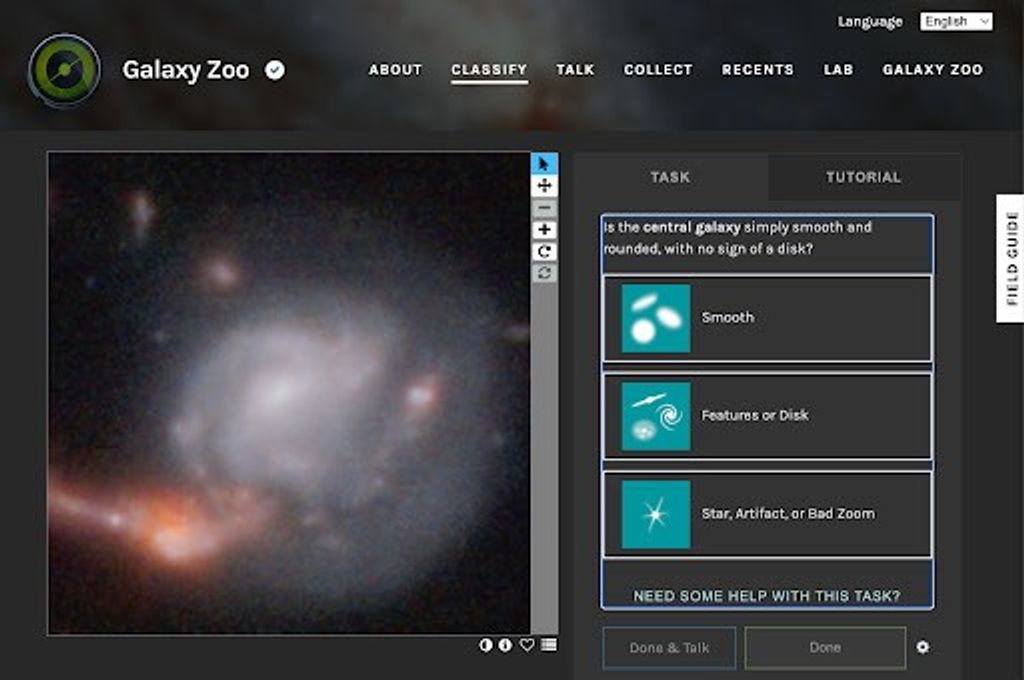

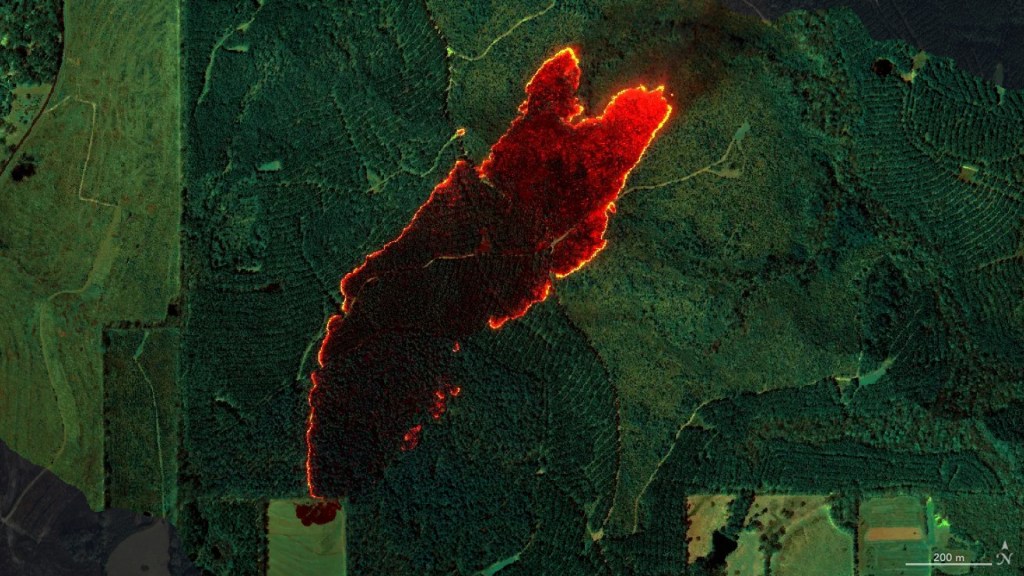

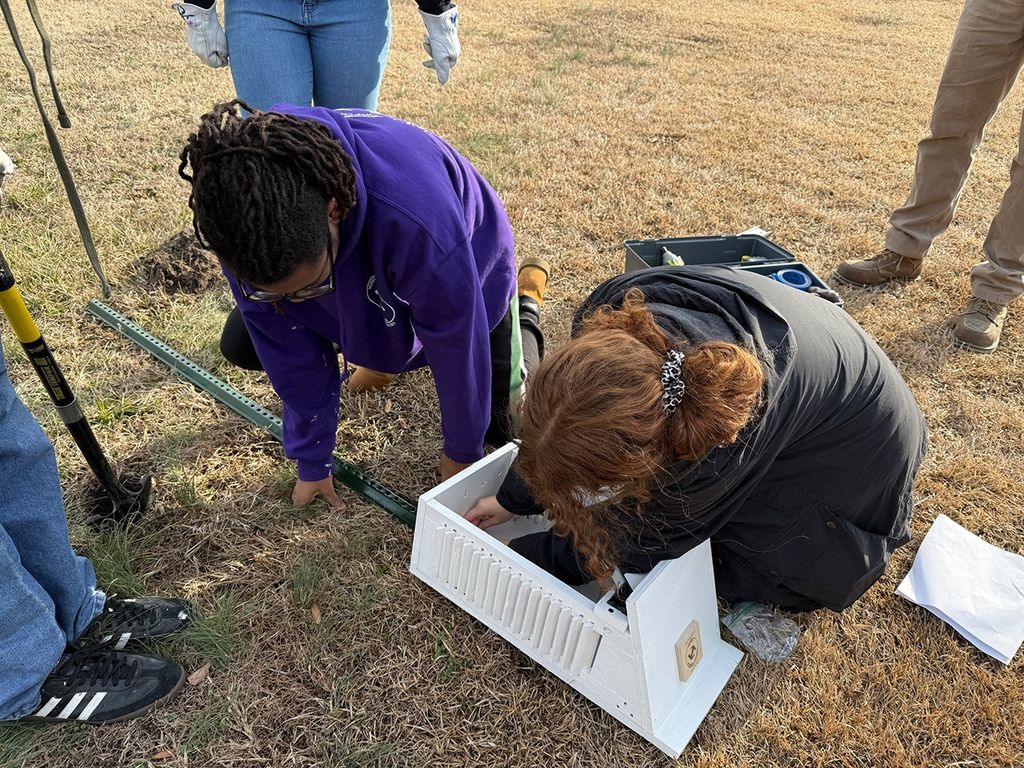

A cell phone, a computer—and your curiosity—is all you need to become a NASA citizen scientist and contribute to projects about Earth, the solar system, and beyond. Science is built from small grains of sand, and you can contribute yours…

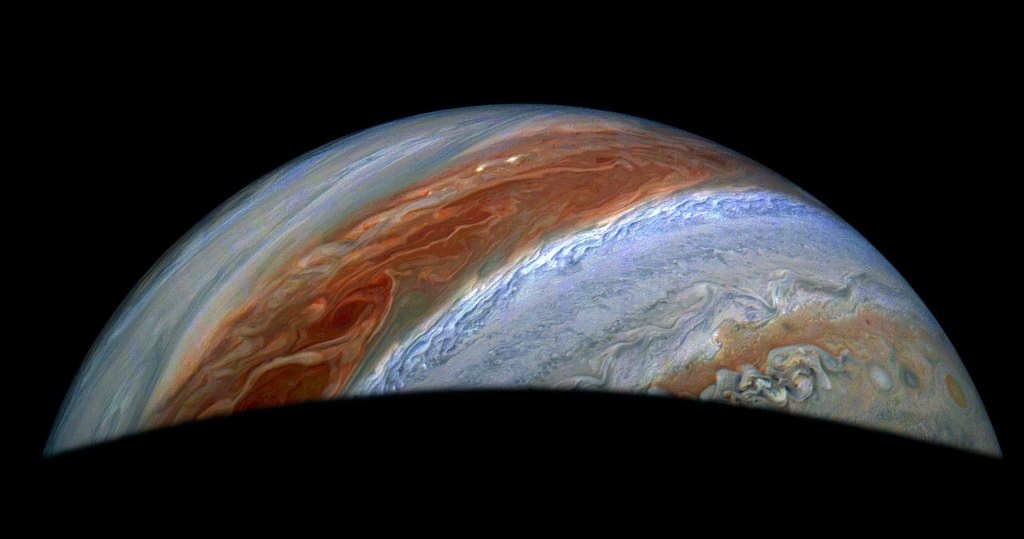

New data from the agency’s Jovian orbiter sheds light on the fierce winds and cyclones of the gas giant’s northern reaches and volcanic action on its fiery moon. NASA’s Juno mission has gathered new findings after peering below Jupiter’s cloud-covered…

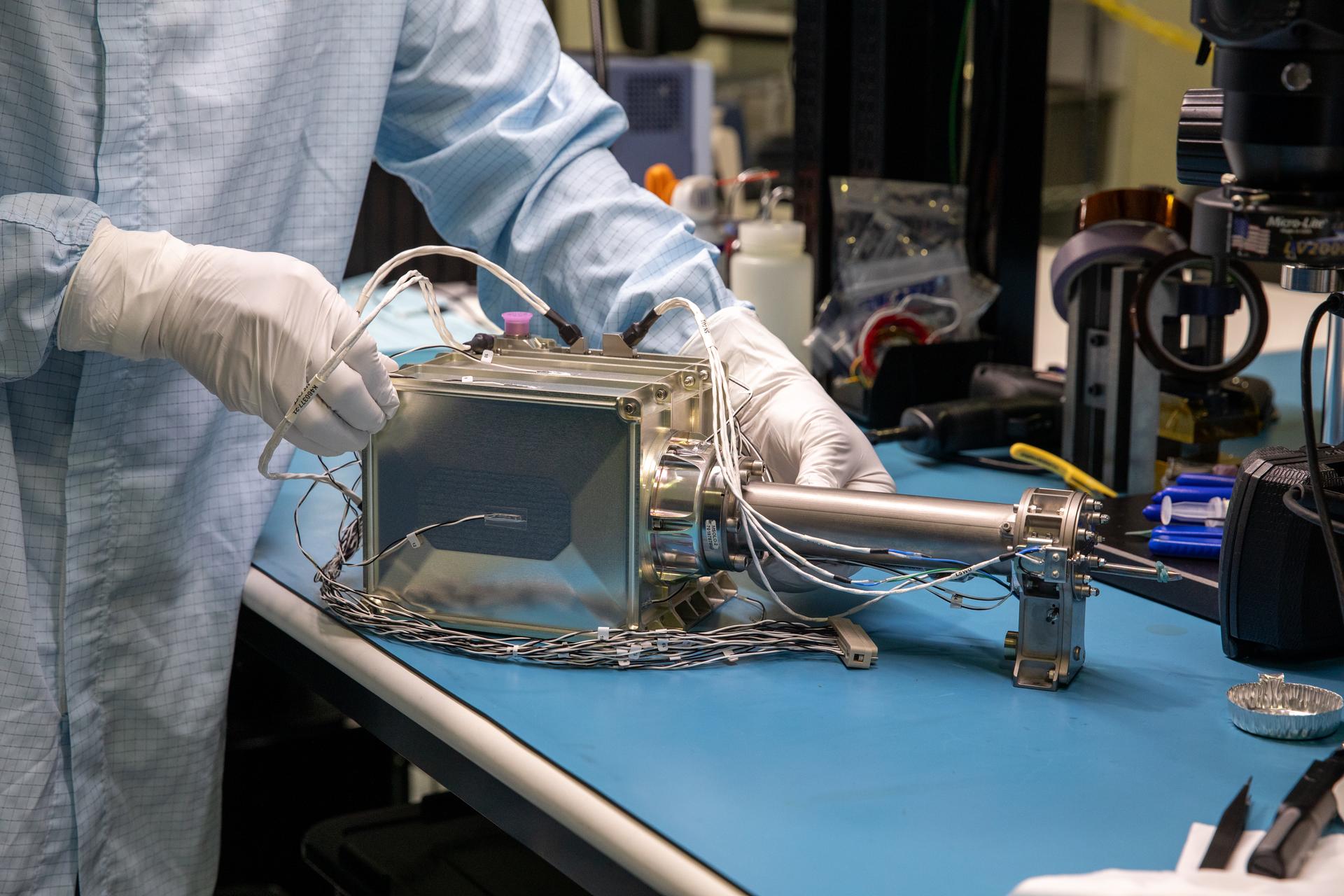

A NASA-developed technology that recently proved its capabilities in the harsh environment of space will soon head back to the Moon to search for gases trapped under the lunar surface thanks to a new Cooperative Research and Development Agreement between…

How are we made of star stuff? Well, the important thing to understand about this question is that it’s not an analogy, it’s literally true. The elements in our bodies, the elements that make up our bones, the trees we…

NASA continues to mark progress on plans to work with commercial and international partners as part of the Gateway program. The primary structure of HALO (Habitation and Logistics Outpost) arrived at Northrop Grumman’s facility in Gilbert, Arizona, where it will…

A JPL facility built to support potential robotic spacecraft missions to frozen ocean worlds helps engineers develop safety tests for next-generation spacesuits. When NASA astronauts return to the Moon under the Artemis campaign and eventually venture farther into the solar…

NASA’s Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope team shared Thursday the designs for the three core surveys the mission will conduct after launch. These observation programs are designed to investigate some of the most profound mysteries in astrophysics while enabling expansive…

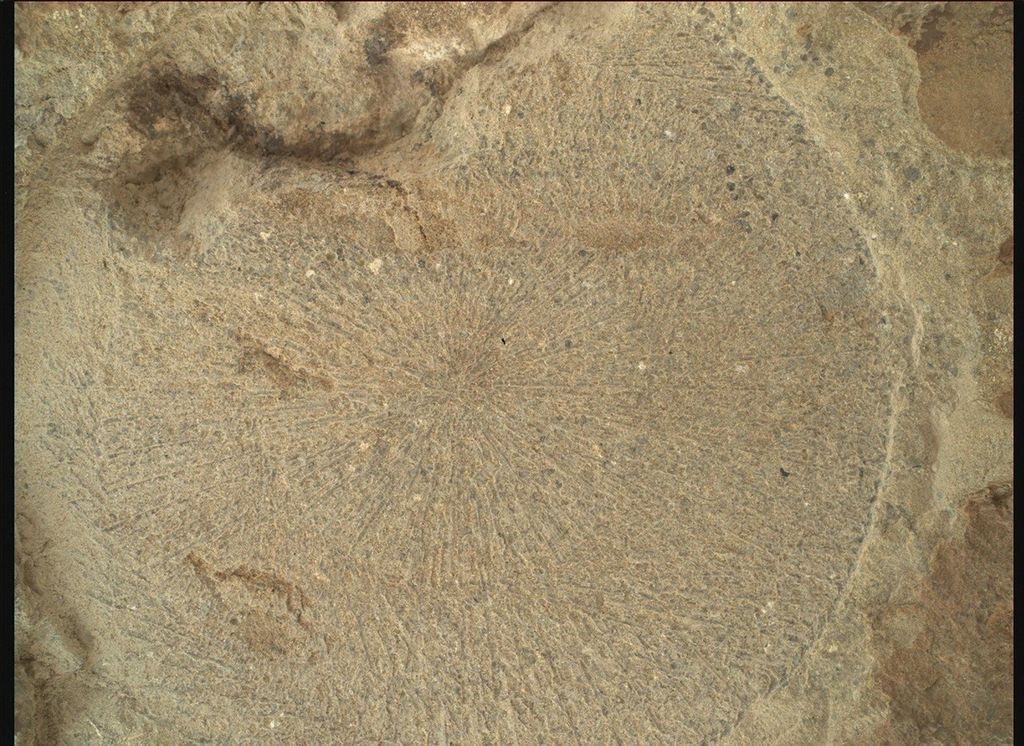

The image marks what may be the first time one of the agency’s Mars orbiters has captured the rover driving. NASA’s Curiosity Mars rover has never been camera shy, having been seen in selfies and images taken from space. But…

In celebration of the Hubble Space Telescope’s 35 years in Earth orbit, NASA is releasing an assortment of compelling images recently taken by Hubble, stretching from the planet Mars to star-forming regions, and a neighboring galaxy. After more than three…

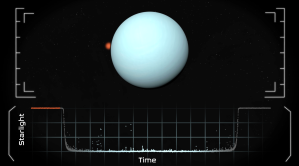

When a planet’s orbit brings it between Earth and a distant star, it’s more than just a cosmic game of hide and seek. It’s an opportunity for NASA to improve its understanding of that planet’s atmosphere and rings. Planetary scientists…