4 min read

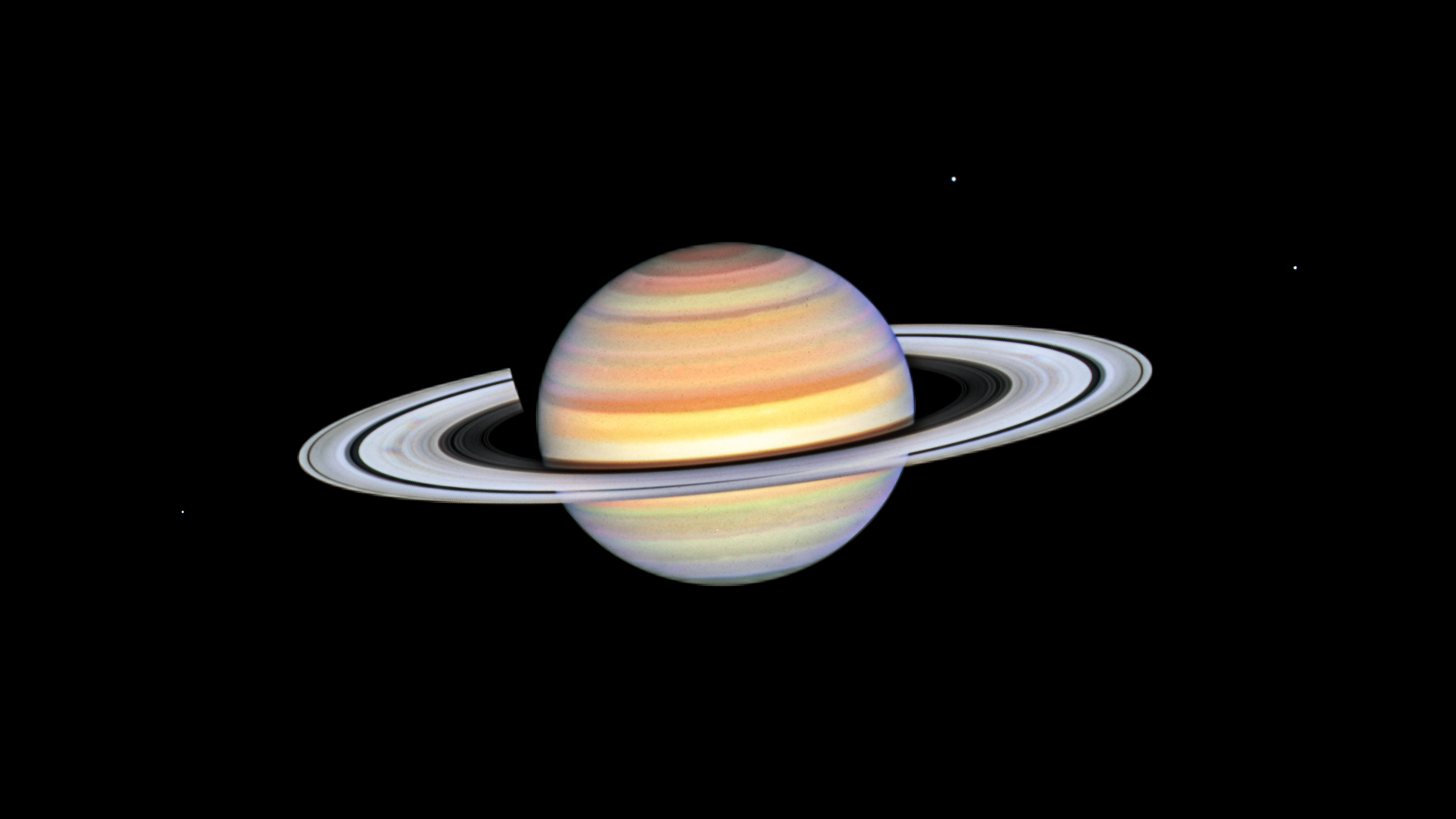

Cassini scientists studying Saturn's rings have made several new findings that further our knowledge of how this beautiful and dynamic system continues to evolve before our eyes.

"Understanding the dynamics of Saturn's rings provides on a miniature scale a better understanding of how our solar system formed from a disk of particles surrounding the Sun," said Dr. Jeff Cuzzi, Cassini interdisciplinary scientist, NASA Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif.

Artist's concept showing Saturn's rings and major icy moons. |

Cassini's composite infrared spectrometer has found that particles within Saturn's main rings (the A, B, and C rings) are spinning slower than anticipated. This occurs even in areas where particles are so densely packed that they frequently bump into each other and where researchers expected them to spin quicker. From the planet outward, the order of Saturn's rings is D, C, B, A, F, G and E. The rings were assigned a letter in the order they were discovered

Scientists determined the spin rate by studying the temperature profiles of the particles. They hypothesized that collisions in the dense A and B rings would have resulted in faster-spinning ring particles that would have a more uniform temperature. Instead, results show that the A and B ring particles spin slowly, just like particles in the sparser C ring.

"It would be wonderful if we could scoop up a ring particle and bring it back to Earth to study it but we can't do that, so using an instrument like this one can help reveal what a ring particle might actually look like," said Dr. Linda Spilker, deputy project scientist for the Cassini-Huygens mission at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif. "A ring particle probably looks more like a fluffy snowball than like a hard ice cube," she said.

Saturn's outermost main ring, the A ring, is also causing a stir. Cassini's ultraviolet imaging spectrograph shows that particles in that ring are trapped in ever-changing clusters of debris. These clusters are torn apart and reassembled by gravitational forces from the planet, indicating that the A ring is primarily empty space. The particle clusters range from the size of sedans to moving vans.

"The spacing between the clumps is greater than the widths of the clumps themselves," said Dr. Joshua Colwell, team member of the ultraviolet imaging spectrograph, University of Colorado, Boulder. "If we could get close enough to the rings, these clumps would appear as short, flattened strands of spiral arms with very few particles between them."

Colwell likened the process to a handful of marbles placed in orbit around a beach ball. The marbles closest to the ball would orbit more quickly and drift from the pack before reorganizing themselves into new, orbiting clumps.

Imaging scientists have also made some surprising discoveries. Part of the D ring (the ring closest to Saturn) has gotten dimmer and moved inward, toward Saturn, by about 200 kilometers (125 miles), since it was observed by NASA's Voyager spacecraft, some 25 years ago.

Dr. Matt Hedman, an imaging team associate at Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y. said, "Cassini's high resolution images of the D ring are providing new information about the dynamics and lifetimes of ring particles in a new regime, very close to the planet."

Possible object in Saturn's F ring. |

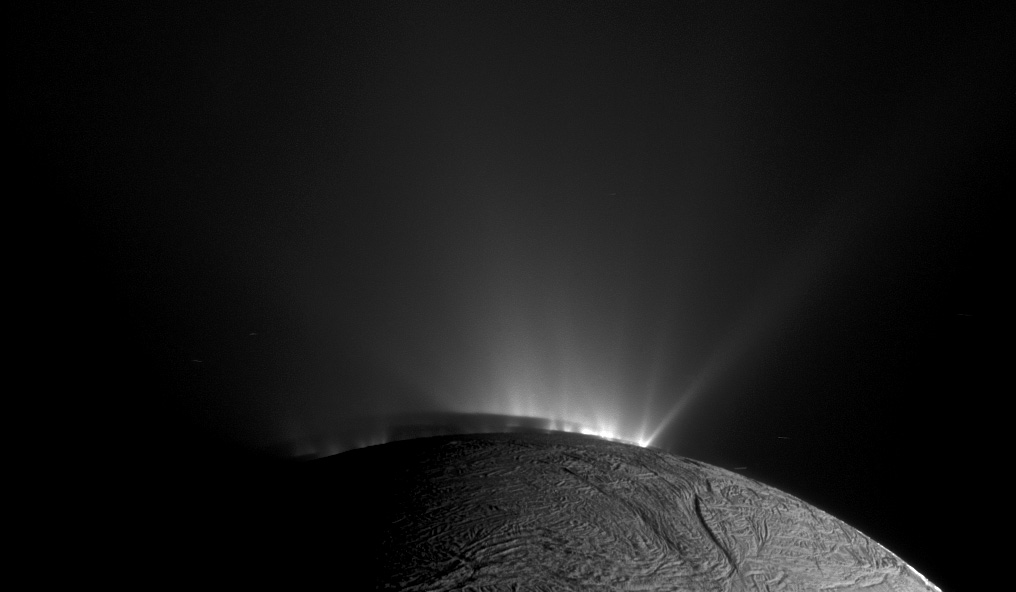

Among their biggest surprise is that a spiral ring encircles the planet like a spring. This unexpected "spiral arm" feature exists in the vicinity of the F ring and actually crosses the F ring's orbit.

"It is very possible that the spiral is a consequence of moons crossing the F ring and spreading particles around," said Dr. Sebastien Charnoz, imaging team associate at the University of Paris. "The F ring might be a very unstable or even a short-lived structure."

These ring results were acquired over the summer as Cassini was in a favorable ring-viewing period after the spacecraft's orbit was raised to look down on the rings. These and other results were presented in a press briefing at the 37th Annual Meeting of the Division for Planetary Sciences meeting held this week in Cambridge, England.

More information on the Cassini-Huygens mission is available at http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov and http://www.nasa.gov/cassini.

The Cassini-Huygens mission is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, manages the Cassini-Huygens mission for NASA's Science Mission Directorate, Washington, D.C. The Cassini orbiter was designed, developed and assembled at JPL.

Contact:

Carolina Martinez (818) 354-9382

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.