Solar System Exploration Stories

Filters

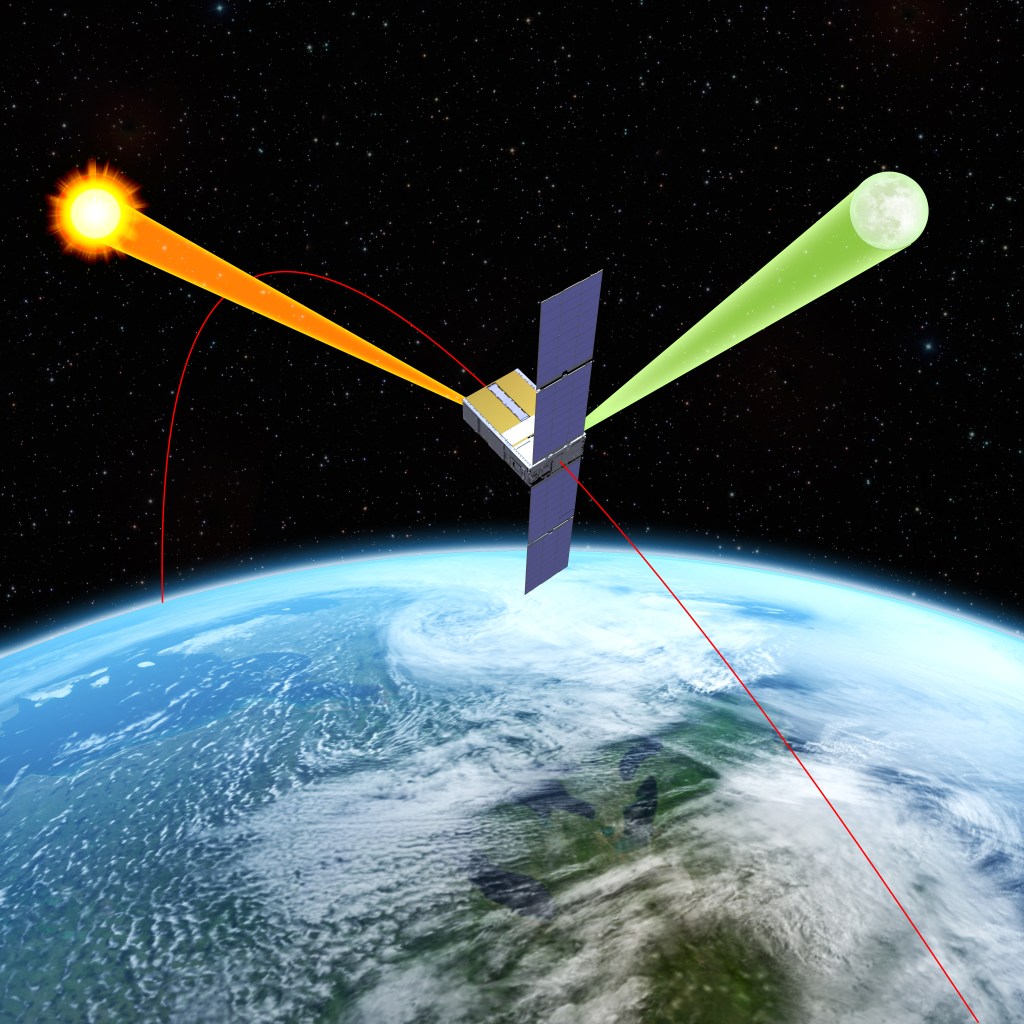

NASA will soon launch a one-of-a-kind instrument, called Arcstone, to improve the quality of data from Earth-viewing sensors in orbit. In this technology demonstration, the mission will measure sunlight reflected from the Moon— a technique called lunar calibration. Such measurements…

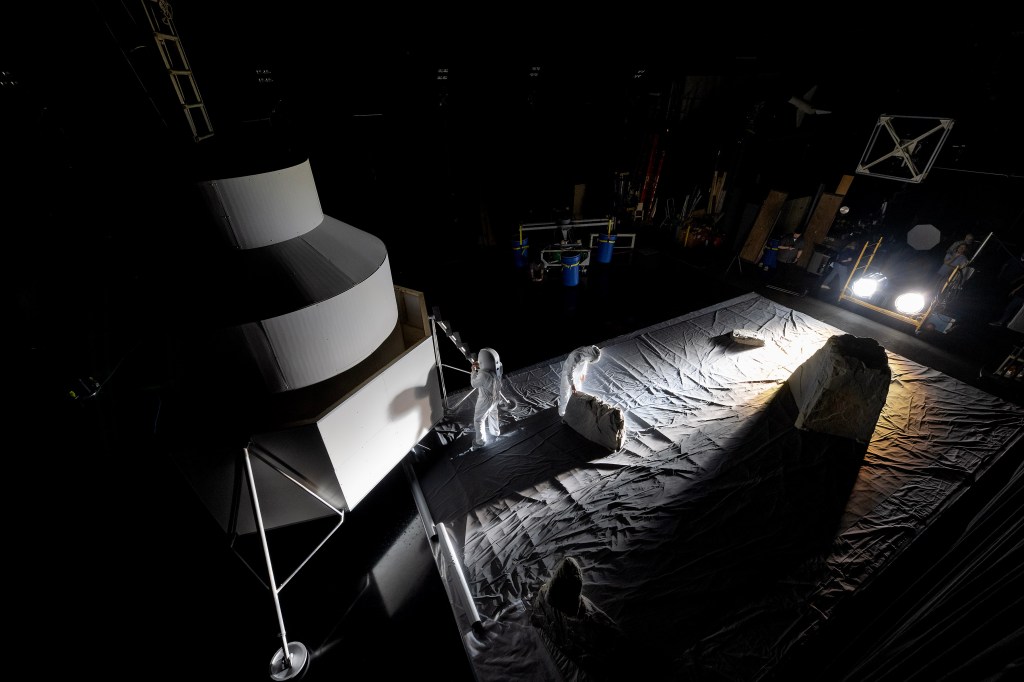

On June 11, NASA’s LRO (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) captured photos of the site where the ispace Mission 2 SMBC x HAKUTO-R Venture Moon (RESILIENCE) lunar lander experienced a hard landing on June 5, 2025, UTC. RESILIENCE was launched on Jan.…

.jpg?w=300&fit=clip&crop=faces%2Cfocalpoint?w=300px)

from NASA’s Heliophysics Education Activation Team (NASA HEAT) and the Astronomical Society of the Pacific/Night Sky Network Have you ever wondered about what the Sun is made of? Or why do you get sunburned on even cloudy days? NASA’s new…

NASA is launching rockets from a remote Pacific island to study mysterious, high-altitude cloud-like structures that can disrupt critical communication systems. The mission, called Sporadic-E ElectroDynamics, or SEED, opens its three-week launch window from Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands…

The 2001 Odyssey spacecraft captured a first-of-its-kind look at Arsia Mons, which dwarfs Earth’s tallest volcanoes. A new panorama from NASA’s 2001 Mars Odyssey orbiter shows one of the Red Planet’s biggest volcanoes, Arsia Mons, poking through a canopy of…

Planets, Solstice, and the Galaxy Venus and Saturn separate, while Mars hangs out in the evening. Plus the June solstice, and dark skies reveal our home galaxy in all of its glory. Skywatching Highlights All Month – Planet Visibility: Daily…

by Kat Troche of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific Here on Earth, we undergo a changing of seasons every three months. But what about the rest of the Solar System? What does a sunny day on Mars look like?…

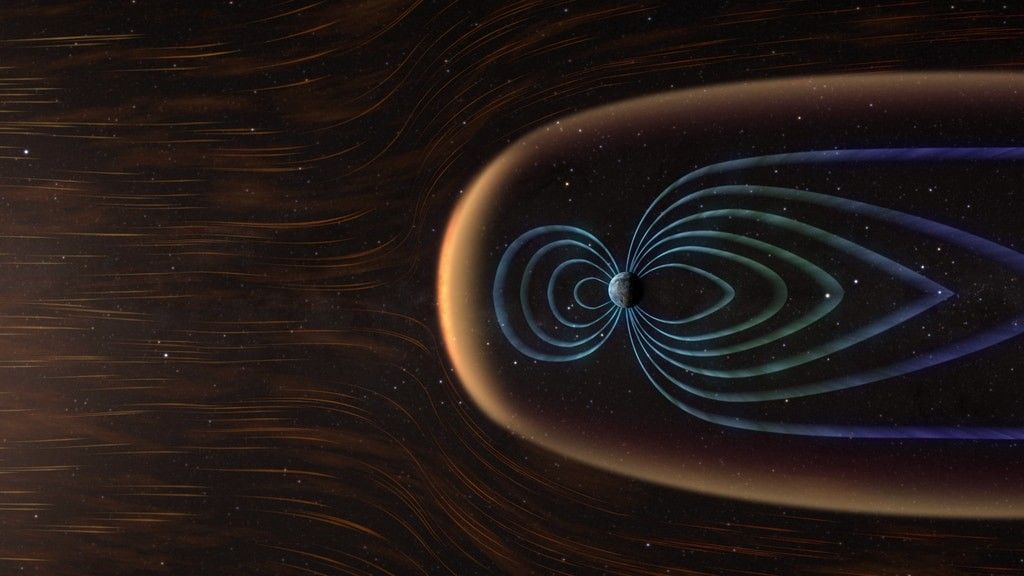

After a decade of searching, NASA’s MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere Volatile Evolution) mission has, for the first time, reported a direct observation of an elusive atmospheric escape process called sputtering that could help answer longstanding questions about the history of water…

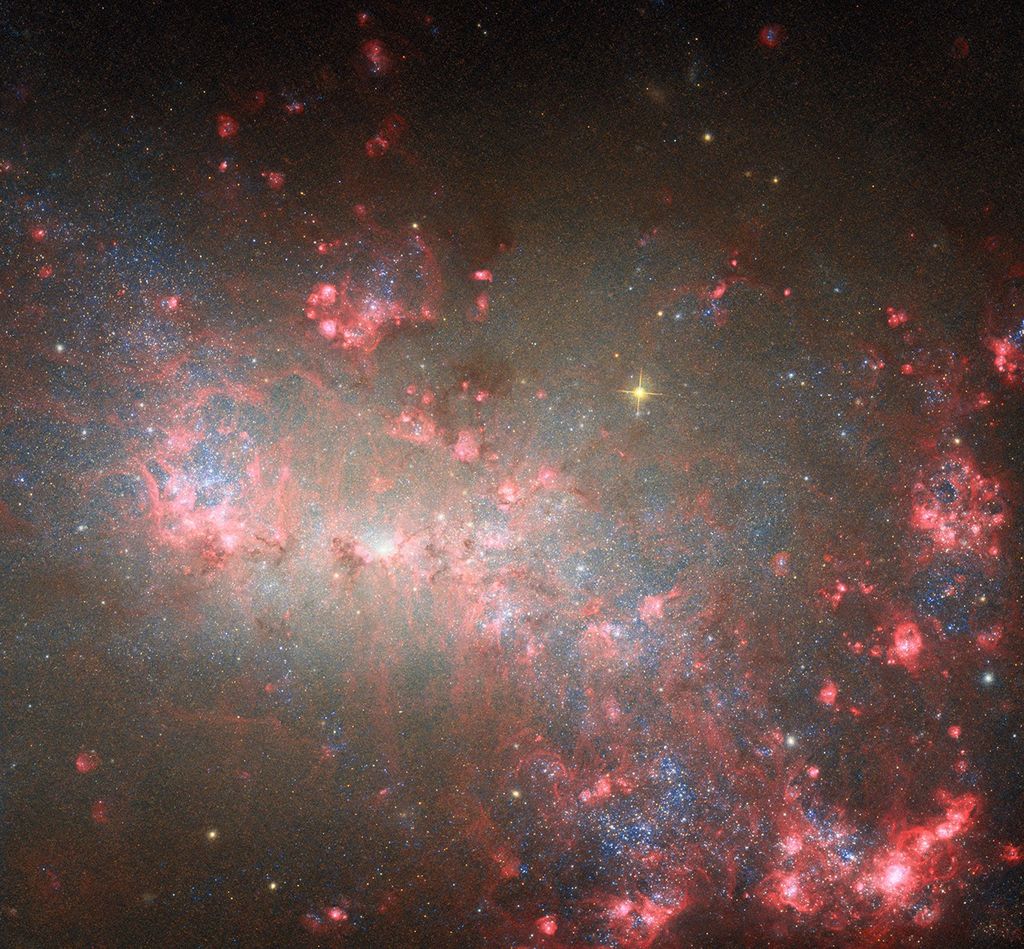

A new NASA study reveals a surprising way planetary cores may have formed—one that could reshape how scientists understand the early evolution of rocky planets like Mars. Conducted by a team of early-career scientists and long-time researchers across the Astromaterials…

When it descends through the thick golden haze on Saturn’s moon Titan, NASA’s Dragonfly rotorcraft will find eerily familiar terrain. Dunes wrap around Titan’s equator. Clouds drift across its skies. Rain drizzles. Rivers flow, forming canyons, lakes and seas. But…

.jpg?w=1024)