Titan: Exploration

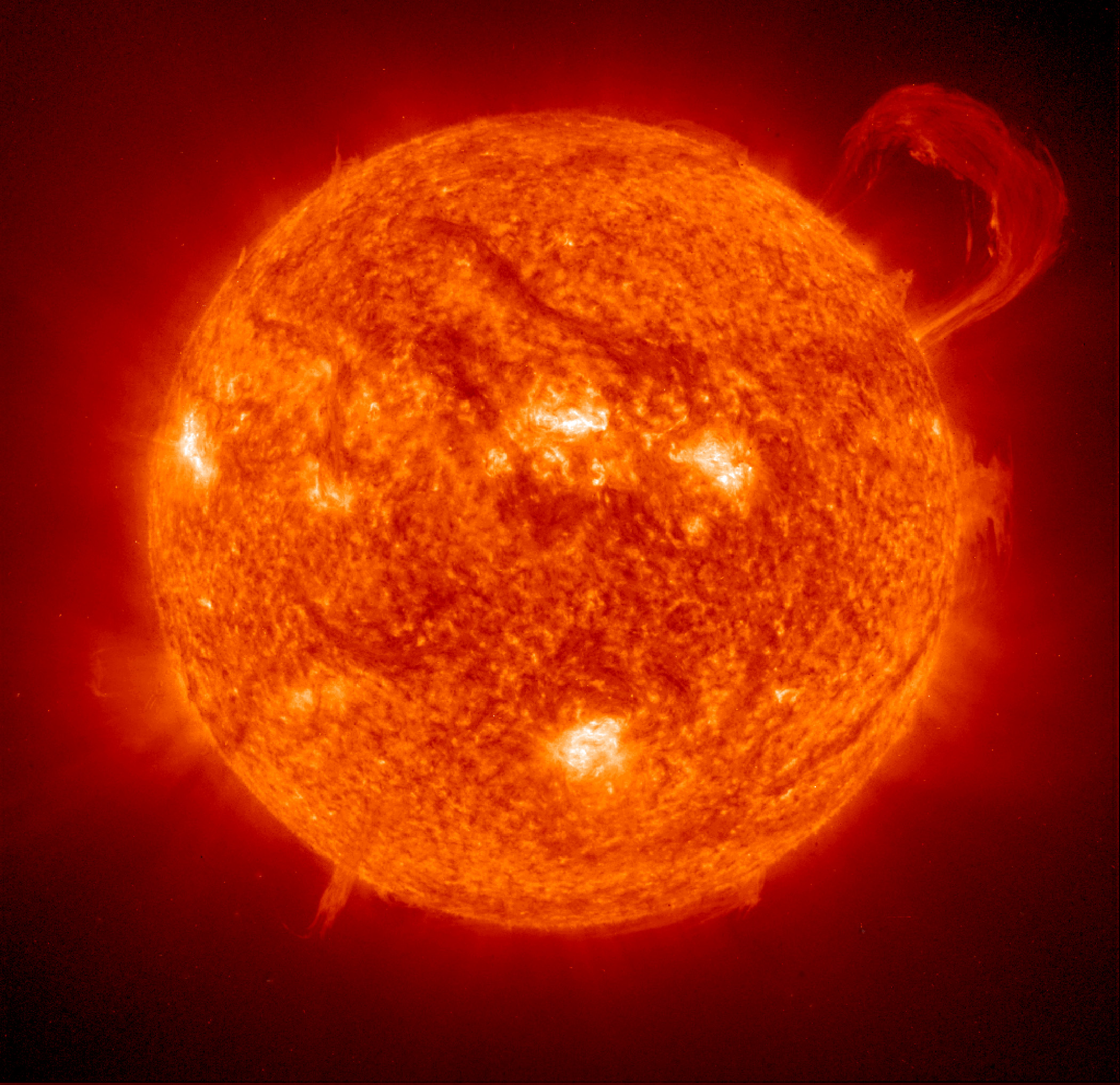

Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens discovered Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, on March 25, 1655. It was nearly 300 years later, in 1944, when Dutch-American astronomer Gerard Kuiper discovered one of the characteristics that makes Titan exceptional: this distant moon actually has an atmosphere. Kuiper made the discovery by passing sunlight reflected from Titan through a spectrometer and detecting methane. Further telescope observations from Earth showed that Titan’s atmosphere was dense and hazy.

The first spacecraft to explore Titan, Pioneer 11, flew through the Saturn system on Sept. 1, 1979. Astronomers on Earth had previously studied Titan’s temperature, and calculated its mass, and Pioneer 11 confirmed those characteristics. Because of Titan’s extended and opaque atmosphere, scientists at the time thought (incorrectly, it turns out) that Titan might be the largest moon in the solar system. Pioneer 11 also saw hints of a bluish haze in Titan’s upper atmosphere, which scientists predicted the Voyager spacecraft would be able to see.

When the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft passed through the Saturn system in 1980 and 1981, they couldn’t see Titan’s surface because of its hazy atmosphere—images from that mission showed a featureless orange world—but they did see the blue haze as a seemingly detached layer of Titan’s upper atmosphere. Just before Voyager 1 arrived in the Saturn system, some scientists speculated that the moon’s cold temperatures and methane meant that Titan might be home to oceans of liquid hydrocarbons. But the Voyager spacecrafts’ cameras were unable to penetrate Titan’s opaque atmosphere to get a clear view of the surface. Voyager did, however, reveal that Titan had traces of acetylene, ethane, and propane, along with other organic molecules, and that its atmosphere was primarily nitrogen.

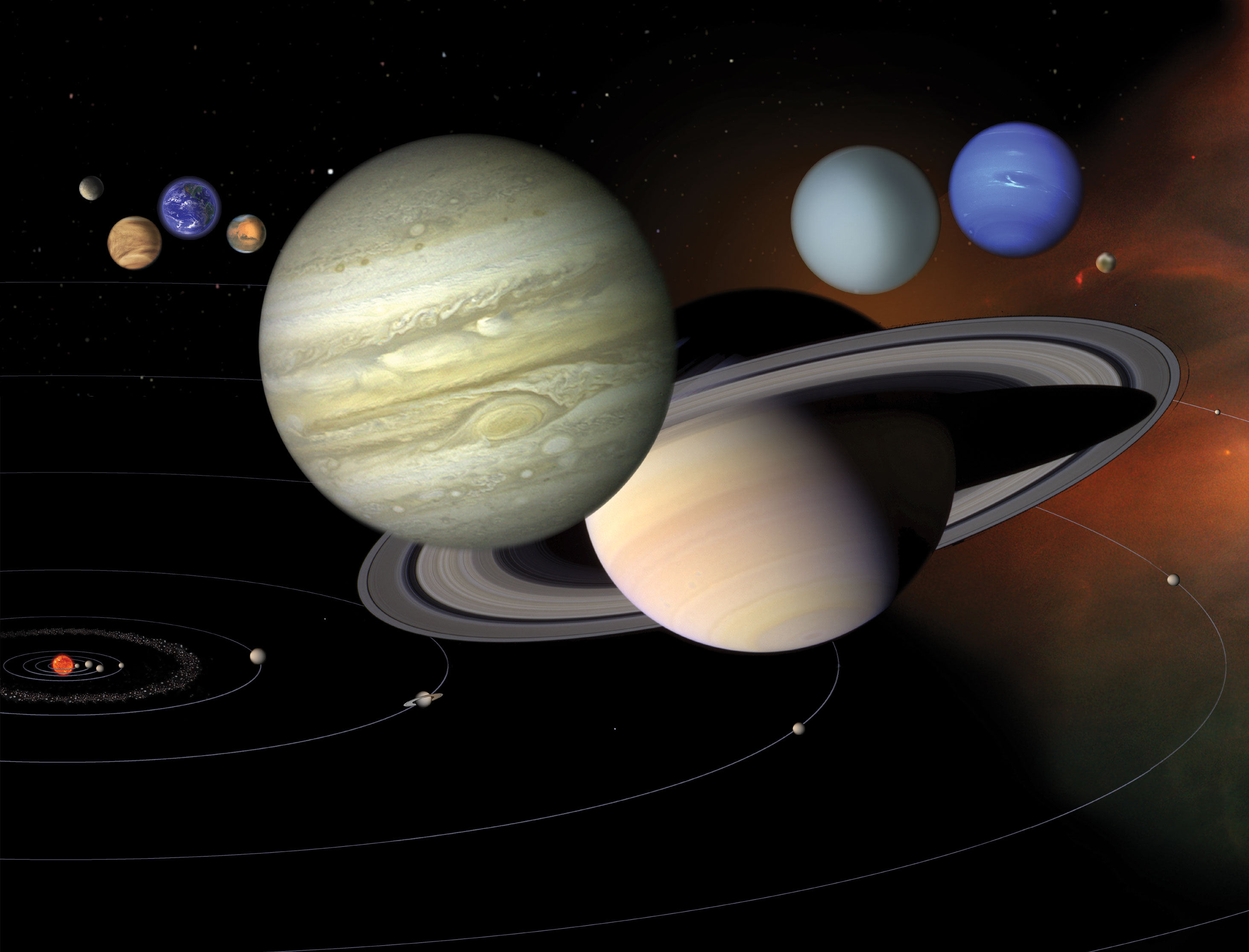

Voyager 1 also finally provided a measurement of Titan’s surface temperature and air pressure, as well as the moon’s radius, revealing Titan to be the second largest moon in the solar system, not the largest, which is Jupiter’s Ganymede (both moons are larger than Mercury). The Voyagers also saw a distinct difference in brightness from north to south, which was presumed to be a seasonal effect—a presumption that was later confirmed.

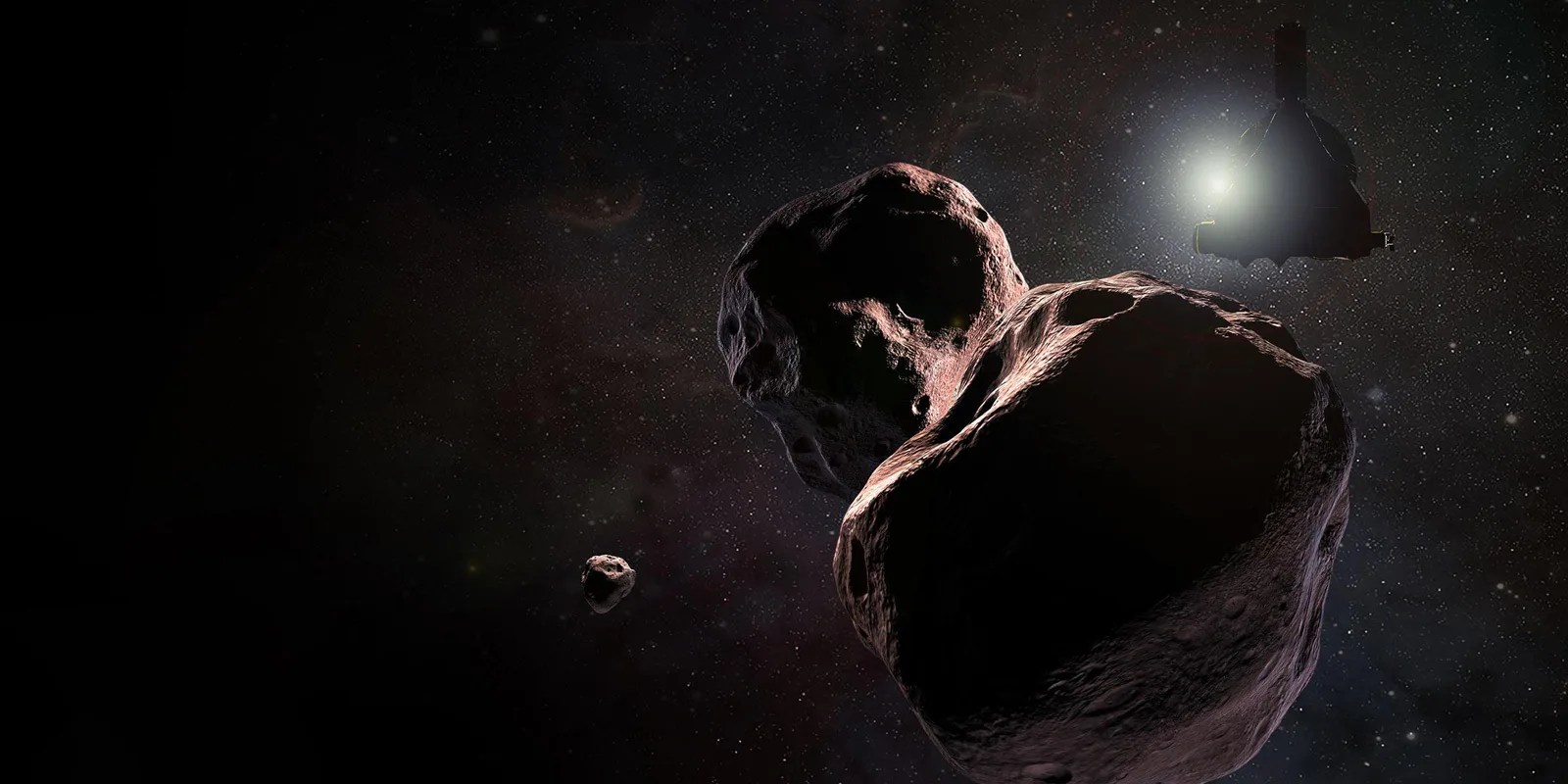

In 1994, NASA's Hubble Space Telescope recorded pictures of Titan using particular colors of infrared light that could pierce through the haze. The Hubble images showed large bright and dark areas, including bright region the size of Australia. The Hubble results didn't prove that liquid seas existed, though, and the mystery about what was hidden below Titan’s haze remained until 2004.

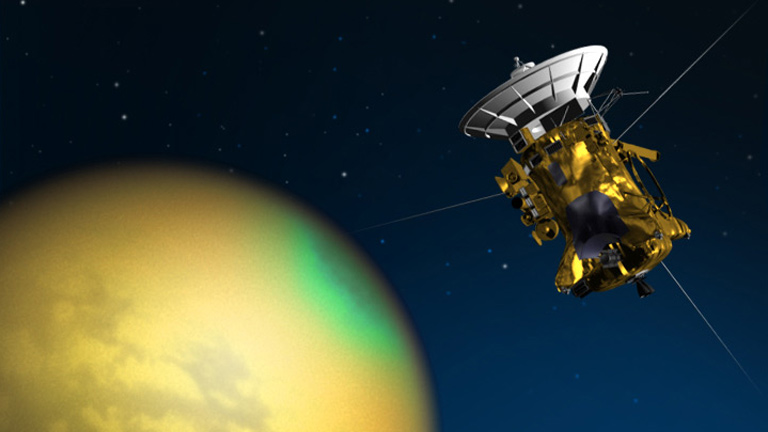

The Cassini spacecraft, with the European Space Agency’s Huygens probe attached, became the first human-made object to orbit Saturn in 2004. Almost immediately, Cassini began observing Titan, peering through the haze for the first time. The Huygens probe detached from Cassini and parachuted through Titan’s atmosphere, landing on the surface on Jan. 14, 2005—the first landing of a probe in the outer solar system. Huygens collected images and atmospheric data during its descent as well as from the surface, and transmitted that data to Cassini, which relayed the data to Earth. Cassini performed 127 close flybys of Titan over 13 years, using a suite of tools, including radar and infrared instruments to peer through Titan’s haze and finally give scientists a detailed view of the moon’s surface and complex atmosphere. Cassini-Huygens discovered that Titan has clouds, rain, lakes and rivers of liquid hydrocarbons, as well as a subsurface ocean of salty water.

Explore in 3D—Eyes on Cassini

Using the free “Eyes on Cassini” interactive visualization on your Mac or PC, you can ride along with the Cassini spacecraft for all of its flybys of Titan. You can see Titan the way different instruments on the Cassini spacecraft saw it. You can even see how the inside of Titan might be layered based on Cassini data. “Eyes on Cassini” allows you travel with Cassini at any time during the entire mission, a period of about 20 years. For example, watch the arrival at Saturn on July 1st, 2004, or see Cassini launch the Huygens probe and follow Huygens to Titan. You can see where Cassini was when it captured iconic images, and you can compare the real images to the visualization. You can even ride along with Cassini during its final 22 orbits, in which it zips between Saturn and its rings—a place no spacecraft had explored before. And you can watch these things happen at actual speed, or much, much faster.