Genesis

Type

Launch

Target

Objective

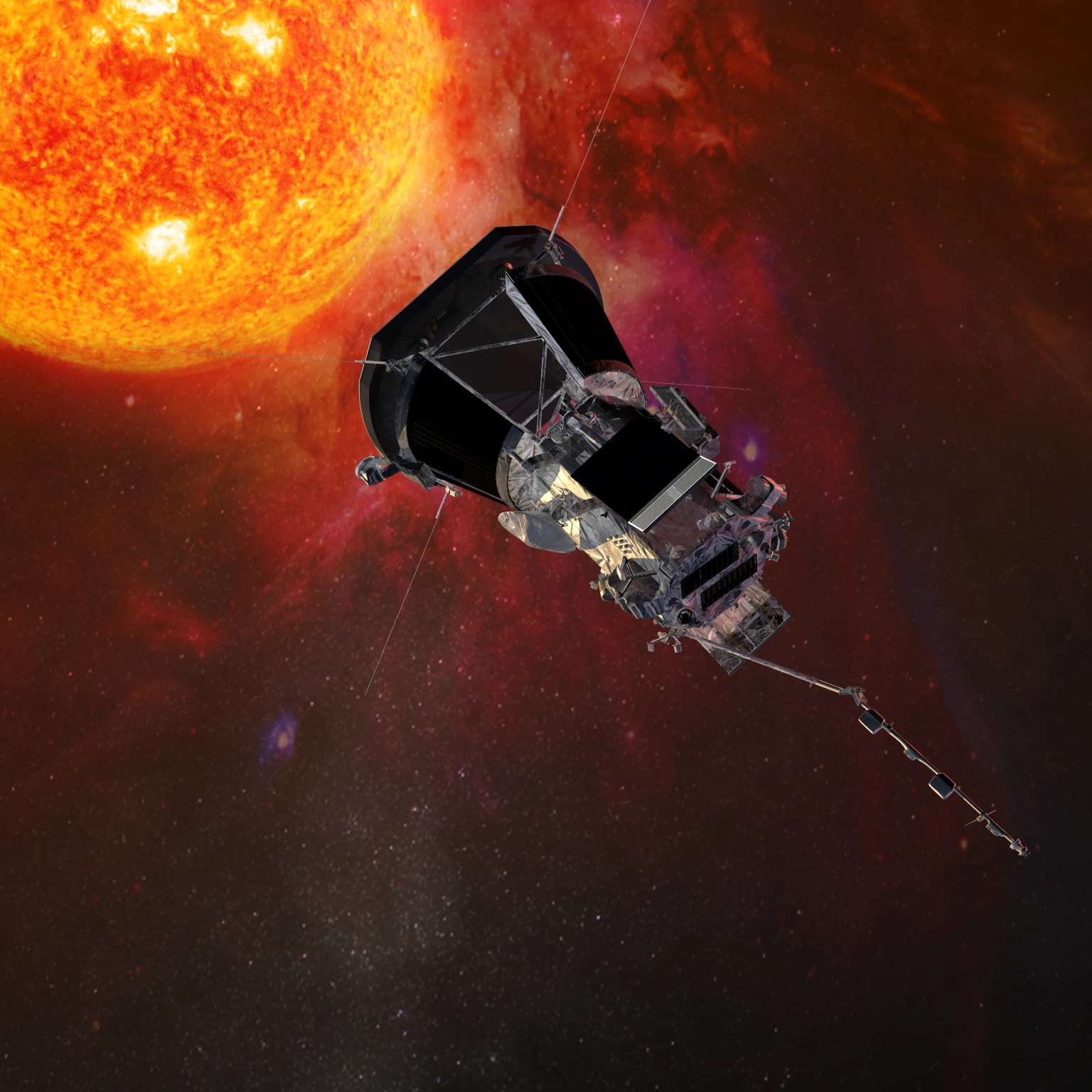

What was Genesis?

NASA's Genesis spacecraft spent more than two years collecting samples of the solar wind. The spacecraft then brought the sample canister back to Earth where it parachuted to the ground. Despite a hard landing in the Utah desert, the Genesis samples were recovered.

| Nation | United States of America (USA) |

| Objective(s) | Solar Wind Sample Return, Sun-Earth L1 Lagrange Point |

| Spacecraft | Genesis |

| Spacecraft Mass | 1,402 pounds (636 kilograms) |

| Mission Design and Management | NASA / JPL |

| Launch Vehicle | Delta 7326-9.5 (no. D287) |

| Launch Date and Time | Aug. 8, 2001 / 16:13:40 UT |

| Launch Site | Cape Canaveral, Fla. / SLC-17A |

| Scientific Instruments |

|

Key Dates

Aug. 8, 2001: Launch

Sept. 8, 2004: Sample return capsule lands in Utah

In Depth: Genesis

Genesis, the fifth Discovery-class spacecraft, was designed to collect samples of the solar wind and then bring them to Earth.

The collection device, fixed inside the sample return capsule, was made of a stack of four circular metallic trays, one that would be continuously exposed, and the other three deployed depending on particular solar wind characteristics.

After insertion into a low parking orbit around Earth, the third stage fired exactly an hour after launch, at 17:13 UT Aug. 8, 2001, to send the spacecraft toward its destination at the Sun–Earth Lagrange point, or L1.

On Nov. 16, an engine burn lasting about four minutes put Genesis into a halo orbit around L1 with a radius of about 497,000 miles (800,000 kilometers) and a period of six months.

The first array was exposed for sample collecting on Nov. 30, while the other arrays were exposed from 193 days (coronal mass ejection collector) to 887 days (the bulk arrays).

The prior record for a solar wind collector was on Apollo 16 in 1972 for a short 45 hours.

All the trays were stowed away April 1, 2004, and exactly three weeks later, on April 22, the spacecraft fired its four thrusters and began its long trek back via an unusual trajectory that took it past the Moon (at a range of about 155,000 miles or 250,000 kilometers), Earth (at about 244,000 miles or 392,300 kilometers), and then to Lagrange point 2 (L2), which it reached in July 2004.

Swinging around L2, it headed toward Earth. About 5.5 hours before re-entry on Sept. 8, the spacecraft ejected the return capsule and then fired thrusters to enter a parking orbit around Earth, partly as a precaution in case the capsule had failed to separate.

The capsule successfully separated and hit Earth’s atmosphere, experiencing a force of 27 g. The drogue parachute (which would have deployed the main chute) did not deploy, and the capsule hit the ground at an estimated speed of 193 miles per hour (311 kilometers per hour) at 15:58 UT Sept. 8, 2004.

The capsule landed as planned at the Dugway Proving Ground in the Utah Test and Training Range, but it was severely damaged and contaminated.

The shattered sample canister was taken to a clean room and, during the subsequent month, carefully disassembled. Teams eventually tagged 15,000 fragments of the return capsule.

Despite the condition of the capsule, during the next several years, project scientists were able to glean a significant amount of data from the recovered debris. They published results detailing, for example, the identification of argon and neon isotopes in samples of three types of solar wind captured by the spacecraft.

An investigation into the accident found that the drogue failed to deploy due to a design defect that allowed an incorrect orientation during assembly of the gravity switch devices that initiated deployment of the spacecraft’s drogue parachute and parafoil.

The main Genesis spacecraft headed back to L1 and entered a heliocentric orbit. Contact was maintained until Dec. 16, 2004.

Key Resources

Siddiqi, Asif A. Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958-2016. NASA History Program Office, 2018.

Legacy Genesis Mission Website